Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part series on Hall of Fame racer Ron Shuman. Read part two in the next edition of the SPEED SPORT Insider.

As we witness the turbulence in the sprint car racing world, many are reminded of how the World of Outlaws challenged the status quo and precipitated a sea-change in the sport.

Anyone with a cursory interest in history learns that the so-called “big three” during the formative days of the Outlaws were Steve Kinser, Sammy Swindell and Doug Wolfgang.

Without question that trio posted impressive numbers. However, one star from that period may be overlooked. In fact, when considering the totality of accomplishments across a range of disciplines, it is clear Ron Shuman deserves greater attention.

While he called Tempe, Ariz., home, Shuman was born on Sept. 15, 1952, in nearby Mesa because of his mother Nadine’s preference in hospital. Ron’s father, Bill, owned an auto repair shop and was a race fan. Catching the bug, Ron’s older brother, Billy, began hanging around owner Dave Birmingham’s Ramada Inn midget racing team.

It was a successful operation with drivers such as Jerry McClung at the controls. The Shuman brothers first cut their teeth on motorcycles, but they soon made their mark with four wheels.

The racing environment was vastly different when the Shumans began climbing the sport’s ladder.

“In Arizona at the time every gas station, even if it was in the middle of nowhere, had a stock car. Billy either found his car behind a gas station or in a junkyard,” Ron Shuman recalled.

That car became the white No. 88 Shuman’s Auto Clinic modified. After Billy got the car in racing shape, Lealand McSpadden became his chief mechanic. When Billy Shuman was ready to move on, he sold the piece to McSpadden. The final domino fell when McSpadden acquired a sprint car ride and let Ron Shuman try the car.

Amazingly, three Arizona legends all began their careers in the same car.

After getting his feet wet, Ron Shuman was ready to take the next step. Lending a hand, his father secured a frame from Jimmy Blanton and got his son’s first modified car in order.

“Out here if you were a pretty good racer you were going to drive somebody else’s race car,” he said. “In Arizona in the 1970s not a lot of people owned their own race car and drove them. It was mostly guys who had a lot of money. They wanted a race car and wanted to hire someone to drive for them.”

He was a quick study.

Racing for Lowell Carsten’s Speedmart team, Shuman was a winner at the imposing Manzanita Speedway by 1973 and the one-lap track record holder. By 1975, Shuman was racing for Bill Boat and he had already bagged an Arizona Racing Ass’n title. His career was ready to explode.

In his first full season with his new group, Shuman finished third in Manzanita points and eagerly anticipated the race once named the Western United States Championship, soon to be known to many simply as the Western World.

Now, in the shadow cast by the Knoxville Nationals and Kings Royal, few contemporary fans can grasp how big this race was. In the 1975 edition of the Western World, Shuman was the fastest qualifier but unfortunately blew an engine.

Boat borrowed an engine from a local drag racer and the crew worked non-stop to get a backup car ready. His performance on Friday landed him in the third row for the 50-lap finale. Getting to the front would be a tall order as 13 of the 26 starters are now members of the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame.

In storybook fashion, in just his third season in sprint cars, Shuman topped one of the biggest races in the land.

By 1976 Shuman harbored dreams of cracking the field at the Indianapolis 500. It wasn’t a pipe dream. In November 1975, he had a chance to test an Indy car at Phoenix Raceway under the watchful eye of Lloyd Ruby.

“They had to put carpet behind my back so I could reach the pedals and I get out there and was hyperventilating,” Shuman explained.

Plans were set for Shuman to drive a car owned by Lindsey Hopkins, but the deal disappeared when his sponsorship money from Lincoln Thrift went away.

In the short-track world, Shuman scored for Speedy Bill Smith of Eagle, Neb., and had even greater success with Phoenix-based constructor Gary Stanton, including a significant victory in the Pacific Coast Nationals at Ascot.

In 1977, still pursuing his Indy car dreams, Shuman headed to Indiana and worked for Hopkins and his talented mechanic Mike Devin. He was a classic gopher but was lauded by all when he used his carpentry skills to reengineer the doors on the classic if antiquated Gasoline Alley garages.

Making effective use of his time away from the Brickyard, Shuman scored his first USAC midget win at Little Springfield in Illinois, but was most productive in the John Ricke and Stan and Tom Hill-owned R&H Farms sprint car.

He bagged a preliminary night win at the Knoxville Nationals in August, and keeping the momentum going in October he beat Jimmy Oskie and Rick Ferkel to win his second Western World. One week later he was a repeat winner of the Pacific Coast Nationals at Ascot.

Shuman shocked USAC’s regulars when he won a July 4, 1978, midget race in Reading, Pa., driving for Dan Pool, and then swept the card by muscling a sprint car fielded by Don Siebert to victory.

After winning again with Pool at Kokomo (Ind.) Speedway, Shuman set the stage for perhaps the most productive year of his Hall of Fame career.

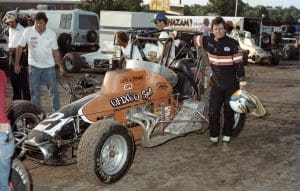

Shuman began 1979 with a pair of World of Outlaws wins in Florida behind the wheel of the No. 721 car owned by successful Texas businessman and racing enthusiast John Mecom and his associate, Tulsa Firestone dealer John Kalb. However, the bulk of his sprint car success came with old friend Gary Stanton.

Shuman claimed 29 victories over the course of the year, including the Knoxville Nationals. During this great run, he also displayed his pragmatic streak.

There were those who proclaimed Shuman knew the dollar value of every position on the race track.

It turns out that’s not far from the truth.

“I wanted to know what it paid to win, what it paid to run 10th, and what it paid to run last,” he said. “I looked at the payout, so I would calculate if it was worth it to make this move to run second or third. Listen, you are sitting in a guided missile that weighs 1,300 pounds and has 750 horsepower, and of course they have more now, and you are rocking and rolling out there. I grew up at Ascot and it seemed people got killed there every year.”

After his fifth victory of the WoO season, Shuman confronted series leader Ted Johnson regarding how much winning the series title would pay. The figure proved to be far less than Shuman hoped, leading to a change in itinerary.

“In June, the Outlaws were going to go to Chico and Petaluma and I didn’t like little race tracks,” Shuman said. “I didn’t grow up on them. Lanny Edwards put a deal together where we could run six nights in eight days or something like that. Stanton and I put a pencil to it, and I said if we could get a couple of grand to show up and win most of these races, we will make more than if we won the World of Outlaws championship.

“We took off and won five out of six and the one we didn’t win was at Houston. I just took the lead but had to pull in. I thought we had blown the engine, but Tommy Sanders was helping us, and he takes the mag and starts flicking it against the cage and he says here’s your problem.”

A five-race winning streak culminated with a harrowing non-winged victory at the Belleville (Kan.) High Banks.

“Back then we screwed the tires on the wheels with metal screws,” Shuman recalled. “It had rained and the cushion is only built up to about halfway, but it is a ledge. I swear I was praying going into turn three every single lap. I won the race easily and I could have gone a lot faster if I wasn’t scared about the right-rear tire falling off the wheel.”

To top the year off, Shuman joined forces with car owner Larry Howard and scored his first Turkey Night Grand Prix triumph. Joining Howard’s team was one of the best decisions he ever made.

“Larry was the tire guy when I first went to Ascot,” Shuman said. “I had learned something from Jan Opperman. He won a lot of races because of tires, so I always tried to be friends with tire people. When you do that, you can get some stuff that other people don’t get.”

In time no one would dominate America’s oldest midget race like Shuman. In 1979 and ’80, his mount was a car Stanton built called a fidget. It was a Volkswagen-powered craft that featured a low center of gravity. Shuman won four consecutive Turkey Night races in the revolutionary car.

Larry Slutter, a mechanical wizard, believed he could develop a Cosworth engine for midget racing and worked closely on the project with Ron Weeks and Howard. It became one of the most renowned cars in the country. All told Shuman won the Turkey Night Grand Prix a staggering eight times.

It was great to have top-flight equipment at his disposal, but this was also the kind of race Shuman loved.

“I don’t care who I drove for I always told them don’t worry about me the first half of the race because I was just getting comfortable,” Shuman explained. “If I’m running second or close to a guy that means I’m not running very hard because it is a 100-lap race. A midget isn’t supposed to go 100 and I’m babying it.”

During the early 1980s Shuman diversified his portfolio. For example, in 1982 he topped another premier midget race when he carried Nick Gojmeric’s car to victory in the Hut Hundred at the Terre Haute Action Track.

“The race was on a Sunday and I had to be in San Jose on Wednesday so I thought, ‘OK, I will run this midget and make a couple of hundred bucks for gas money.’” Shuman said. “Well, Nick heard what I said, and he thought maybe I was going to lay back and stroke it. Well, we were pretty exciting. It was really wet and there were a lot of red flags but as the track got slick, I got faster.”

Shuman got his first taste of USAC Silver Crown racing in 1977 and he eventually found work with several top-flight owners, including Siebert, Howard and George Middleton.

He had a real shot at the 1982 title with an owner who also backed his sprint car operation. While on the road with Stanton and the Mecom/Kalb sprint car, Shuman regularly received assistance from two young hopefuls from Tulsa named Tony Armstrong and Harold Harris.

“If they could get to a race they would help us,” Shuman recalled. “They would get fuel, scrape mud and they became like family to us.”

Armstrong found a spot on Lloyd K. Stephens’ OFIXCO team and one day informed Shuman that engine builder and team leader Steve Carbone needed a driver.

“Carbone wanted someone who could compete with Steve Kinser and Sammy Swindell on the Outlaws trail and I became a cheerleader for Shuman nearly every day,” Armstrong explained.

Shuman was a hot property in sprint car racing, a fact underscored at the end of 1981 when he captured an unprecedented third Western World for owner John Siroonian. It is hard to know how much Carbone had to be convinced to hire the Arizonian. Nonetheless, for the next five years this new combination was one of the most recognizable teams on the World of Outlaws tour.

During the early part of the 1982 season, Shuman spent a great deal of time in the Indianapolis area racing for Jack French and Mark Todd. A USAC victory came at the Indianapolis Fairgrounds mile.

However, in this same year he nearly fulfilled his dream of winning the USAC Silver Crown championship. His first series win came at the 4-Crown Nationals at Eldora Speedway and he left Ohio with the points lead. The finale was scheduled six days later in Nazareth, Pa. Unfortunately, numerous delays led to the race being run on the first Saturday in December.

Two days of rain led to a late start while a series of mishaps, including a serious accident, and impending darkness forced the checkered flag to be waved just past the halfway mark.

An already difficult day ended on a sour note, with Shuman dropping to third in the final standings.

While the OFIXCO team perhaps fell short of its goals, it was still a formidable squad. In 1983 and ’84, Shuman finished fourth in the final rundown and was one position better over the next two seasons.

Amid his best days in the Stephens car, Shuman offered hints that someday he might choose to take his career in a new direction. In a break from its early days, the World of Outlaws had become strictly a winged sprint car series.

“I liked the non-winged car better,” he said. “Because I felt I had more of a say whether I was going to win a race or not.”

In 1985, the California Racing Ass’n embarked on a nine-day tour of the Midwest beginning at I-70 Speedway in Odessa, Mo., and then traveled east for co-sanctioned races with USAC. Shuman had no trouble taming the banks, which caught the attention of CRA President Gary Sokola.

“At I-70 I won a heat with all four wheels in the cushion and Sokola came down and said we could all get a head start to Putnamville (Lincoln Park Speedway) if we just paid you now,” Shuman recalled. “I told him I was all for it. In the feature I lapped up to Jimmy Oskie and Bubby Jones.”

By the time he signed in at Lincoln Park, Shuman was more than confident.

“I was the cockiest I was in my whole career that night,” he acknowledged. “I ran four wheels in the cushion getting into the first turn, drove down and caught the bottom of the good stuff in two and lifted the wheels a little and set the track record.”

A broken birdcage in the feature ruined his night, but he was looking forward to a trip to Terre Haute the next day for the Tony Hulman Classic. In a race that was televised on ESPN, Shuman put on a master class. Patiently working out his own line on the high side, he eventually moved around Larry Rice to win USAC’s most storied sprint car race.

By the end of the 1986 campaign, Stephens announced he was leaving the sport. Shuman signed with Casey Luna’s Ford-powered sprint car team with veteran Kenny Woodruff serving as the crew chief.

It didn’t work out.

“He had the car built specially for the Ford engine and he thought he was going to have to make it tighter, so he raised the motor up,” Shuman said. “Well, it made it tighter, but the motor weighed more in the heads. So, the biggest part of the weight of that car was eight inches above the center of the car. He made the engine higher, which I hated because it made the car tighter and I hate tight race cars. I like them loose, so I could drive them around anywhere I wanted.”

An Outlaws win at Williams Grove Speedway was a bright spot, but Shuman admits for most of the year he “was just pissed off because I didn’t have a good ride.”

Not only was his luck about to change, but in the end his next move ultimately opened a whole new world to him.

Note: Read part two of Pat Sullivan’s feature on Ron Shuman in next week’s edition of the SPEED SPORT Insider.