It wasn’t immediately apparent but something clicked, really hard, when Lynn Paxton was watching what his father, Melvin, did for a good time at his garage along Gettysburg Pike in Mechanicsburg, Pa.

It was the closest repair facility to Williams Grove Speedway. Racers gravitated to the Paxton shop, due in part to Melvin’s hobby: He restored antique cars, even though that concept wasn’t fully formed yet, given the fact that in those years vehicles from the 1930s and earlier could still be found on used-car lots.

It grabbed his son and never completely let go. Despite a stellar career racing sprint cars that cemented him forever as one of central Pennsylvania’s all-time greats, Paxton was never a long-distance traveler in the outlaw tradition. He raised a family and built a business.

Paxton is a living link to the sport’s early days, having experienced the enormous technical advances that took the region’s weekly race cars from throwaway coupes with overhead-valve power to today’s apocalyptically shrieking winged 410s. Paxton enjoyed marked success at every level. And those days watching his dad struggle with the old crocks bore rich fruit: While largely retired today at 77, Paxton has long been one of the nation’s most acclaimed restorers of historic oval racing cars.

“I have a picture of me sitting in a 1904 REO, which was the first truck in Mechanicsburg,” Paxton recalled. “He bought that, and he had it for years. Then in 1951, I think, he bought a Model T, which he restored and we still have that. I guess that’s how I got hung up in it.”

Paxton never officially, declaratively, retired from the cockpit. And his precise count of feature wins remains a little nebulous. By his best guess, the wins total around 250, about 225 of which came in sprint cars as they’re defined today. Six were World of Outlaws features, including the first three races the group ran in New York.

On the dirt tracks of Pennsylvania, Paxton thrived under an all-encompassing technological arc that took years to fully manifest itself.

The record includes 11 track titles and a trio of KARS sprint car championships, making Paxton the only driver besides Smokey Snellbaker and Kramer Williamson to capture a KARS title.

It began in 1961, less than a year after Paxton’s hero, the Eastern sprint car icon Tommy Hinnershitz, ended his driving days. Melvin Paxton had begun renting his shop out to local racers, one being Fred Putney, who ran a Class A flathead at Silver Spring Speedway, Mechanicsburg’s other race track.

Silver Spring had scheduled an annual race for mechanics and when Putney’s wrench didn’t show, Paxton coaxed his way into Putney’s car and finished second. Graduating from high school, Paxton bought a 1947 Ford and raced it locally in hobby classes. In 1963, he dropped in the engine from his street Corvette and took another Ford, acquired from Bobby Gerhart, up the road to Selinsgrove Speedway, where he tried to run it against the fuel-injected modifieds.

An axle snapped but the owner of Putney’s car, Harold Hank, decided to lend him a hand.

Hank canned Putney and stuck Paxton in the seat during a time of significant transition in Pennsylvania racing. At Williams Grove, sprint car teams began showing up at the National Open, which was still theoretically a stock car race.

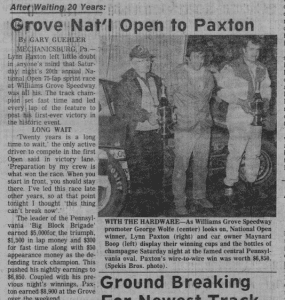

Paxton’s first National Open, in 1963, went to the seriously abbreviated Michigan cutdown of Gordon Johncock, which happened to be topped by a huge plywood wing. Paxton didn’t win in 1964, but the following year, after a National Guard stint, he connected with mechanic Ree Smith — the guy who skipped the mechanic’s race — who supplied him with a new CAE chassis and a Ford engine from Holman-Moody. Paxton captured the first two of his 45 feature wins at Williams Grove consecutively in the CAE car.

At the time, Williams Grove was run by the visionary promoter Jack Gunn as the race cars matured.

These were the supermodifieds or “bugs,” basic open-wheel cars derived partially from modifieds with the same fuel-injected power.

Click below to continue reading.