During a recent Southern Sprint Car Shootout Series event at Florida’s Auburndale Speedway, a quick stroll through the pit area revealed some of the nicest pavement sprint cars in the country.

They showcased excellent craftsmanship, including good welds and unique body panels.

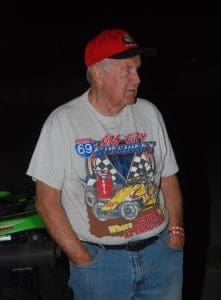

The majority of the cars in the pits on that night featured Jerry Stuckey-built Hurricane chassis. Stuckey might be one of the most underrated car builders in the country. He flies under the radar and doesn’t seek accolades for his work. His personality is modest by all accounts.

Born in Campbellstown, Ohio, in 1946, Stuckey moved around a lot during the early years of his life as his father was a preacher. The family eventually settled in Farmersburg, Ind.

“When I was a senior in high school, over by the Peoria, Ill., area, we ended up going to a county fair in Knoxville, Ill. That was the first time I saw an IMCA sprint car race,” remembered Stuckey. “Watching sprint cars on a dirt track kind of hooked me.”

Shortly after that, Stuckey bought his own sprint car.

“I got it from a guy in Indianapolis. It was just a frame with a front axle. I learned how to weld and built my own stuff,” Stuckey explained. “I went to Grant King’s and he’d bend me a piece of tubing and I’d put it on the car whenever I wanted to fix something.

“I made my sprint car debut at Paragon Speedway,” Stuckey added, recalling his first night of racing. “I thought I was fast but got passed by a lot of cars. But that’s how you learn.

“I began running in 1971 or 1972. My racing was limited to around Indiana — down to Haubstadt, Paragon and Bloomington. When Lincoln Park Speedway in Putnamville came in, we quit running Paragon.

“We would run with USAC when they would come to Terre Haute because we lived only 20 miles from the race track.”

Stuckey didn’t win any features, but he did make a USAC main at Terre Haute. During his driving days, the Indiana sprint car scene was the toughest in the country.

“It was a tough bunch up there,” Stuckey recalled. “I did win a handful of heat races. I was fast qualifier at Paragon in my second year. It was a big deal just to be fast qualifier.”

His first attempt to build a car was a modification of his first sprint car.

“It started with the car I bought from the guy in Indianapolis,” Stuckey said. “I cut it off in half and rebuilt the front half because it wasn’t in the right dimensions. Then, I cut it off and eventually rebuilt the back half. Like I said, I was still getting pieces built and bent by Grant King because I didn’t have a tubing bender. I didn’t have the money, so I had to build my own cars.”

Stuckey moved to Florida in 1985 where he lives today. He brought his race car along with intentions of competing with the Tampa Bay Area Racing Ass’n.

“My wife Vickie was a school teacher and she couldn’t get a job. We knew friends of ours I went to high school with who had moved to Florida. They were teachers,” Stuckey explained. “Construction was booming in Florida but it didn’t pay as much. We kind of got to the point we knew there was racing down there, not as much. I didn’t like cold weather, so everything kind of opened the door to make the move down there.

“When we moved down there, all the racing was dirt. When I was first introduced to pavement, it was through Mac Steele,” Stuckey noted. “He had something he wanted me to rebuild for him. He was converting an old dirt car to a pavement car. Starting out, I built a few TQ midgets in Indiana.

“When I came to Florida, one of the early cars I built was a TQ midget for Mac that his son David drove. That car dominated TQ racing in Florida the two years David drove it.”

Prior to the 1996 season, Stuckey was approached by Tampa car owner Jack Nowling with a proposition to build a specialty pavement sprint car to make an assault on the USAC National Sprint Car Series with David Steele driving.

“Jack and David put it together, the wheelbase and the basic dimensions of the car, and brought it to me. I just finished it off,” Stuckey said. “I’d done some work on Mac’s pavement car to change some things. I adapted some of the things I did on that car to the new car.

“I think one of the reasons they asked me to build the new car was because of all the success David had with the TQ I had built six years earlier. We talked about it. I told them we can build a big car just like we had built a little car.”

The car was fast right out of the box. The maiden voyage of the new Hurricane chassis saw Steele set quick time and win the USAC feature at Lakeside Speedway in Kansas City, Kan.

Two races later, the car set a qualifying record at Phoenix Raceway when he toured the one-mile oval in 26.180 seconds. The team picked up another USAC victory at Winchester (Ind.) Speedway later that year.

The success of the car had others wanting Stuckey to build them a Hurricane.

Since the debut of the Hurricane chassis in 1996, the car has captured numerous TBARA championships as well as the 2022 Must See Racing championship with Charlie Schultz and recent Southern Sprint Car Shootout Series championships with drivers Troy DeCaire, Shane Butler, Davey Hamilton Jr. and Daniel Miller.

In addition, Stuckey’s cars have claimed two Little 500 victories and a handful of poles since first running that event in 1996. Stuckey was inducted into the Little 500 Hall of Fame in 2019.

Every piece of a Hurricane chassis is welded, bent and fabricated by Stuckey. He doesn’t mass produce his chassis.

“It’s hard enough for me to satisfy myself when I build a car,” Stuckey explained. “If I wanted to mass produce them, I’d have to hire somebody. I’d have to stand over them and watch them all day long, and not do anything myself. If I had to guess how many cars I’ve built, I’d say we’re getting close to 100. Before that there were probably 25-30 TQ midgets that we did.

“I don’t do deadlines anymore. I don’t get in any hurry,” Stuckey added. “I just do it as much as I want to. It used to be about 15 years ago I’d do 10 to 12 cars a year if I really pushed on it. Being solo and doing every single part yourself, takes a lot of time.”

Stuckey keeps a silver dollar in his pocket for good luck. He’s had the silver dollar so long it has worn flat on both sides.

“It might be a good luck piece but I’m not sure it changes anything. It started out with my brother Melvin who always carried one,” Stuckey said. “There’s 17 years difference between us in age. He’s the one who taught me how to weld. We did Jeeps and stuff, and I did it with him. I just kind of followed in suit with what he was doing. Carrying it that many years in your pocket shaves that much off of it to make it a slick deal. I reckon it’s been in my pocket probably close to 62 or 63 years.”

When the 77-year-old Stuckey, who resides in Springhill, Fla., was asked how many more years he would continue to build cars he responded, “I’ll do it until I can’t do it. I gotta have something to do. I’m not a fisherman or whatever. I just don’t wanna sit around and watch television. I gotta go out to the garage and do some work.”