Look through the Indianapolis 500 entry lists of the 1950s and ’60s and you’ll find driver after driver who has been all but forgotten.

Even though they didn’t rise to the height of accomplishment achieved by their more esteemed contemporaries, they too were winners who chased their racing dreams with a fierce focus, determination and passion.

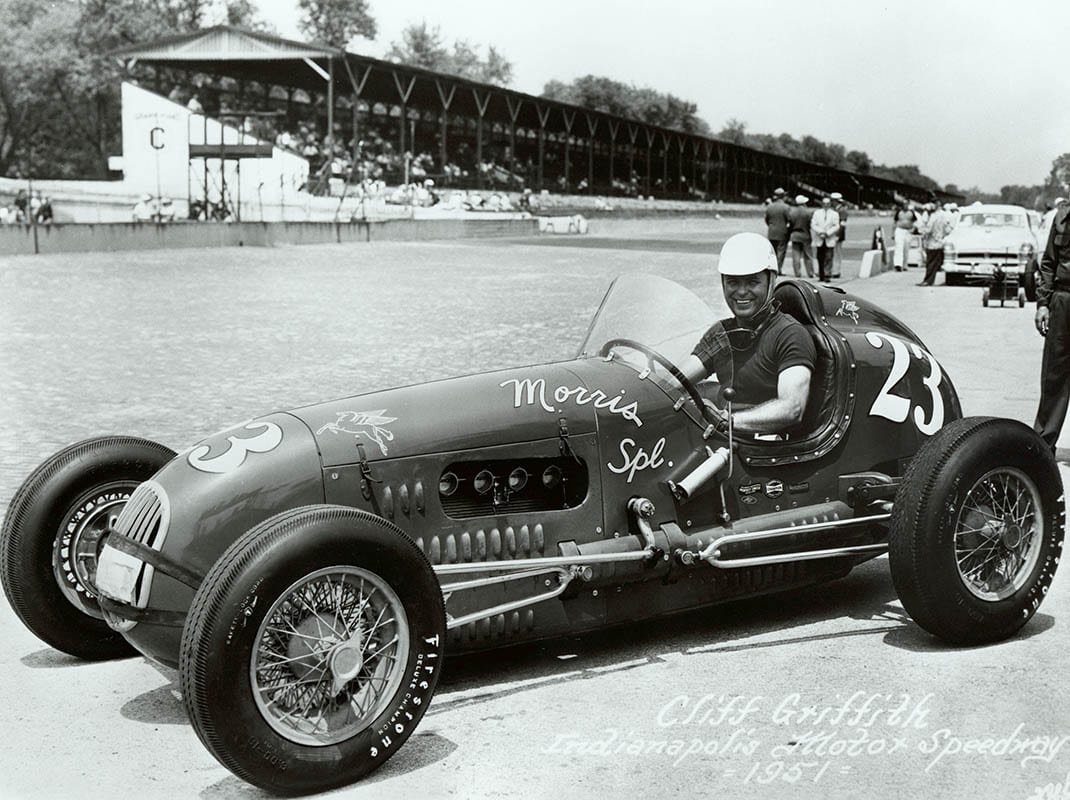

Clifton Reign Griffith was one of these.

Born in Nineveh, Ind., on Feb. 6, 1916, Griffith spent his formative years in and around Indianapolis. Like many young central Indiana boys, he was inevitably drawn to Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

At age 10, he bicycled to the speedway with some of his adventurous buddies. They climbed the trees surrounding the track so they could watch the cars roar past.

Griffith’s hero was 1925 500 winner Pete DePaolo. He not only got to watch DePaolo run, but a compassionate guard sneaked him into Gasoline Alley to meet his hero.

That set the course of his life. He’d become a race car driver.

Toward that goal, Griffith built a sprint car in his shop class at Arsenal Tech High School and attempted to campaign it in the summer of 1934.

His first outing didn’t go well. He spun twice on consecutive laps. Stunned by the embarrassing beginning of what he envisioned to be a heroic racing career, he turned his car over to Les Mundy. Mundy raced it successfully until Griffith sold it to famed sprint car owner Dizz Wilson.

It was three years before Griffith got back into racing. His friend, George Metzler, offered him a ride in his sprint car at the Salem (Ind.) Fairgrounds. It was a turn-around performance. He won his heat and ran third in the feature.

Griffith became a force on the tough Midwest bullrings before and after World War II. Driving Hector Honore’s famed Hal sprinter, the “Black Deuce,” Griffith won 27 features in 1946 and claimed that year’s Midwest Dirt Track Racing Ass’n championship. He repeated as champion in 1947.

Griffith began to make forays into AAA races and, as he extended those activities and had some success, he got a shot at Indianapolis in 1950. Although he only qualified the ancient Sarafoff Special as the first alternate, Griffith was ecstatic. He was on his way.

In 1951, his childhood dreams became reality when he made the exclusive 33-car field. For the 1952 500 he was back with Tom Sarafoff. This time, however, in a better car — Walt Faulkner’s 1950 record-breaker. He qualified in the third row and was running third when the engine faltered near the halfway point of the race.

That impressive showing landed him a top-line ride for 1953 in Ed Walsh’s Harry Stephens-prepared Bardahl Special. The combination proved fast.

During practice, Griffith cut a lap quicker than Bill Vukovich’s pole-winning run. Then suddenly, for a reason he never understood, the car got away from him as he powered off Indy’s notorious turn one.

It pounded the wall twice and erupted into a fireball. Griffith received third-degree burns over 40 percent of his body. The crash knocked out half of his teeth and broke his shoulder, right hand and back. He spent six months in Methodist Hospital and lost 90 pounds.

At one point he said, “I prayed to die.” Most believed he would.

He survived and raced again, but he wasn’t the same. He’d lost something. At least the top car owners believed he had. Stuck in equipment that didn’t match his talent, it was 1956 before Griffith made Indy again.

He qualified the Jim Robbins dirt car in the last row and raced it to a 10th-place finish. It was the last year an upright car qualified for the 500.

Though he tried through 1964, Griffith made only one more Indianapolis 500. In 1961, he started on the last row and headed to the front before a burned piston put him out of the race.

Griffith didn’t achieve all he wanted in racing. He didn’t win the 500, but during an era when just making the race was a career accomplishment, he was one of the rare few who did.

Until his death on Jan. 23, 1996, Griffith insisted racing had given him more than it had taken.