In his younger years John Cooper, the future president of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Daytona Int’l Speedway, ventured to the south for an IMCA sprint car race.

In his younger years John Cooper, the future president of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Daytona Int‘l Speedway, ventured to the south for an IMCA sprint car race.

Standing next to the organization‘s legendary promoter Al Sweeney, Cooper stared with awe at a packed stand full of fairgoers primed for some racing action. With his fertile mind fully engaged, Cooper turned to Sweeney and asked the most basic of questions, “What draws people to these events?”

Sweeney never hesitated. Looking his young protégé in the eye he responded, “The reflected glory of the Indianapolis 500.”

Who knows what direction American auto racing would have taken if three-time Indy 500 winner Wilbur Shaw had failed in his attempt to persuade Terre Haute businessman Anton “Tony” Hulman to save the crumbling Indianapolis Motor Speedway from oblivion?

Yet, by 1946 Hulman and his associates had the venerable plant back in action, and in many ways the Golden Days of the Brickyard awaited.

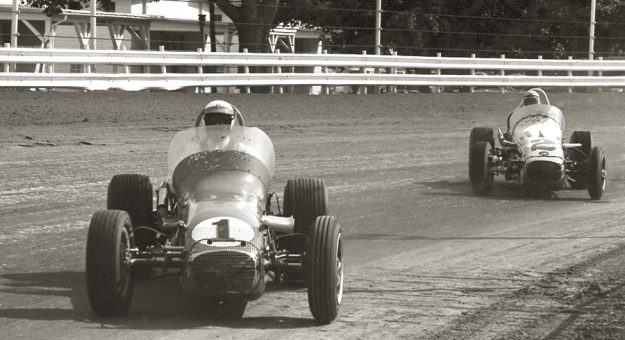

There is probably no single period in the history of the 2.5-mile oval that captured the imagination of fans quite like the roadster era. Beginning with Bill Vukovich‘s heat defying domination in 1953 the roadsters held sway over the nation‘s premier motorsports event for more than a decade.

The rise of the roadster was a product of its time. Many of the master mechanics, fabricators and metallurgists who had worked in the aircraft industry during World War II realized what they had learned about construction and aerodynamics during wartime could be useful to make race cars go faster.

Men such as Frank Kurtis, A. J. Watson, Quinn Epperly, George Salih and Luigi Lesovsky became recognizable faces at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In short order the roadster spelled the death knell for the classic dirt car at Indianapolis.

Nonetheless, the national championship trail was littered with one-mile dirt tracks. Thus, throughout the 1950s fans could find the stars of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway at places such as Bay Meadows and San Jose in California, the Detroit Fairgrounds, Denver‘s Centennial Park and the Arizona State Fairgrounds in Phoenix.

Additionally, the Hoosier Hundred at the Indiana State Fairgrounds was the most lucrative dirt race in the country.

Then came another sea-change. In 1964, A. J. Foyt became the last man to win the Indianapolis 500 in a front-engine car and by that time the handwriting was already on the wall. Dirt tracks such as The Milwaukee Mile and Pennsylvania‘s Langhorne Speedway were paved and gleaming new superspeedways were sprouting across the land.

When Al Unser carried his beautiful George Bignotti-prepared Johnny Lightning Special to victory at the California State Fairgrounds on Oct. 4, 1970, it was the last time a race contested on dirt was included on the national championship schedule.

Some thought the days of the classic dirt car were over. However, to the surprise of some, the United States Auto Club announced a separate series would be established for championship dirt cars. The inaugural season called for races at Nazareth (Pa.) Speedway, the Indiana State Fairgrounds and the one-mile ovals at the Illinois State Fairgrounds and Du Quoin State Fairgrounds. Many doubted the series could survive.

Car owners, drivers and fans proved to be a stubborn lot and did not allow this style of racing to die. Luckily, during the early days of the series superstars such as Foyt, Mario Andretti and Unser refused to turn their back on the dirt cars.

This group handed the baton to a new crop of Indy 500 veterans that included Tom Bigelow, Larry Rice, Pancho Carter and Gary Bettenhausen. Men such as Chuck Gurney, Jack Hewitt and Jimmy Sills relished the chance to take on the vaunted miles. Other future Hall of Fame drivers followed their lead.

Over a half-century has passed since the Silver Crown Series was launched. To remain vibrant required some significant adjustments. Hence, today more races are conducted on half-mile ovals, and pavement dates comprise the majority of the calendar.

Sadly, the Hoosier Hundred, the undisputed crown jewel of the discipline has now faded away, the victim of renovations at the Indiana State Fairgrounds. Now, as difficult as it is to fathom, only two active one-mile dirt ovals, both on Illinois soil, survive.

Still, when you talk to participants, they acknowledge the prestige that comes with winning at Springfield and Du Quoin.

With 18 series wins to his credit and decades behind the wheel, Brian Tyler is one of the old guard. Six times Tyler has taken the checkered flag on the big dirt miles, most recently at Du Quoin in 2021.