I recently had the pleasure of reminiscing with my uncle, Pete Hurtubise.

He recalled fondly those days of working with my dad (Jim), with much emphasis on the 1964 Indianapolis car.

It was an innovative car they believed gave them a legitimate shot at an Indianapolis 500 victory.

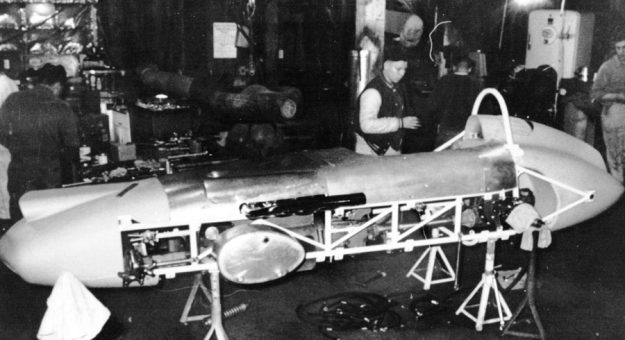

Uncle Pete worked alongside dad to design and build the car from the ground up, literally. They sketched its outline on the concrete floor of their barn on our Shawnee Road property in New York.

The result was an Indianapolis roadster voted the prettiest car at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway that year. It was featured in Custom Car Magazine and became the “centerpiece” for the annual charitable fashion show.

Uncle Pete painted the car a striking red and George Gruber did the lettering. Uncle Pete said they had to lock Gruber in the barn and give him food and lots of alcohol from time to time to keep him working.

Uncle Pete laughed that the more Gruber drank the steadier his hands got.

The finished car was towed to Tombstone, Ariz., to publicize their sponsor, Tombstone Life Insurance. They arranged a photoshoot in front of the Bird Cage Theatre (saloon) along with an authentic Tombstone Marshal, Jack Hendrickson.

As part of the festivities, Tombstone Life gave Uncle Pete two silver dollars. He gave one to dad, and dad bent and riveted it to make the car’s throttle pedal.

In 1964, there was no minimum weight for Indianapolis cars and the objective was to build the lightest car possible to get better fuel mileage, handle better through the turns and accelerate out of the turns quicker.

They met their objective in several ways.

Dad had Louie Senter at Ansen Automotive create machine special aluminum hubs that used six lug nuts to secure the front wheels, rather than the heavier, traditional steel knock-off spinners. Dad wanted to use a similar setup at the rear, but the design of the Halibrand quick-change rear end and axle assembly prevented that.

But Senter manufactured much lighter aluminum brake rotors for the rear. They overlooked no detail in lightening the car, even drilling holes in the gearshift lever and many other components.

Unfortunately, while practicing before time trials, dad crashed and destroyed the front axle. So they went back to the knock offs on the front. They determined the cause of the accident was the shape of the nose-mounted air scoop. It allowed air to lift the front end and dad lost traction.

To correct this, they added two small fins that aerodynamically pushed the nose down.

Taylor Devices — a North Tonawanda, N.Y., business — had designed and built seismic dampers to protect a bridge in China. Using that concept, Paul Taylor, the device’s inventor and company owner, designed a liquid suspension for dad’s car.

It replaced the much heavier torsion bars, and wheel response was reportedly five times faster than that of traditional suspensions.

However, they ran out of time in developing the suspension. Dad didn’t feel secure with it, so they replaced it with coil-over shocks, still lighter than the torsion bars.

Another area they addressed was magneto placement. The Joe Hunt magnetos often failed because they were mounted on the front of the engine and subjected to a tremendous amount of vibration and heat.

At dad’s request, Meyer-Drake modified the Offy’s gear tower, enabling them to run a driveshaft from the tower, through a pilot bearing in the firewall and to the cockpit-mounted magneto. Joe Hunt reversed the magneto’s firing pattern to make this work and they also added an air scoop to direct cooling air to the magneto.

This creative change worked well, but Uncle Pete remorsefully recalled a decision dad made that possibly cost them a shot at the race win. They built two engines, which were ready and tested.

However, Meyer-Drake offered them an experimental Offy with aluminum main bearing webs (normally brass). Dad decided to go with the engine as it was lighter, but they had little time to track test it.

During the race, as the engine heated, the aluminum main bearing webs expanded allowing oil to blow by, forcing excess oil into the crankcase. The oil pump couldn’t handle the flood of oil, and oil blew through every seam in the engine.

The oil pressure dropped and dad was out after 141 laps.

By 1964, tires, whether from Firestone or Goodyear, would last 500 miles. Uncle Pete said he had a $5,000 check from Goodyear in one hand and a $5,000 check from Firestone in the other. Both companies wanted them to run their tires.

Uncle Pete asked dad if they could run Goodyears on the front and Firestones on the back so they could keep both checks. With his unmistakable Jim Hurtubise chuckle, dad said no.

Tires would later become a part of dad’s legacy when he protested against the tire companies for manufacturing high-quality racing tires for certain drivers and not for everyone. He also insisted the money tire companies dumped into racing would skyrocket costs.

Of course, that happened.

The ’64 Roadster carried 115 gallons of alcohol to minimize the number of pit stops. Fifteen gallons of that was in a reserve tank mounted in the engine compartment. Uncle Pete said if that auxiliary tank had held gasoline instead of alcohol, dad wouldn’t have survived the 1964 Milwaukee crash.

For that race, the week after Indy, they installed the original engine. At the beginning of the race, dad, A.J. Foyt and Rodger Ward battled for the lead.

Uncle Pete said dad was very fast and he was just playing games with Ward and Foyt that had the crowd on its feet.

The three were running nose to tail when the rear end locked up on Ward’s leading car. Foyt hit his brakes and dad hit Foyt’s tail, which catapulted him into the wall. Uncle Pete was the first to him and helped put out the fire, but dad was critically burned.

While dad was recovering in the Burn Center in San Antonio, Texas, DVS owners (George Deebs, Bob Voight and Dick Summers) directed Uncle Pete to drive to California and pick up a new rear-engine car. When he arrived at Ted Halibrand’s factory, there were only unassembled cars sitting around. So Uncle Pete finished building the car himself, including the painting.

When dad made his return to racing, he drove that car to a fourth-place finish. He climbed from the car after the race, exhausted, his hands bloody and painful. However, he’d completed one of the most heroic comebacks in sports history.

Because of dad’s accident and other horrible fires in 1964, USAC made several rule changes to improve safety. Minimum car weight, a minimum of two pit stops at Indianapolis, a 40-gallon fuel limit, and self-sealing fuel bladders all became mandatory.

After the Milwaukee accident, they pushed dad’s 1964 car aside and it sat untouched for almost 60 years. It’s now in the process of being restored.

While not as successful as dad and Uncle Pete envisioned, it’s a car that forever changed my dad’s life.