Without question, NASCAR dropped a million jaws when it moved the Busch Light Clash to a temporary track constructed around the gridiron inside the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

The famed stadium is the home of the USC Trojans football team and will host the Olympics for the third time in 2028. It’s not the first time an elite sporting venue has played host to automobile racing.

Shortly after it opened, the Houston Astrodome was the playing field for USAC midgets during the late 1960s. Little cars also ran sporadically at the Polo Grounds, original home of the New York Giants, and CART briefly bumped around the parking lot at the Giants’ second home, the Meadowlands, in New Jersey.

What’s less obvious, and shouldn’t be, is that for a few pivotal years, auto racing intersected with the Negro Leagues of professional baseball at one of the segregated sport’s most hallowed and enduring shrines.

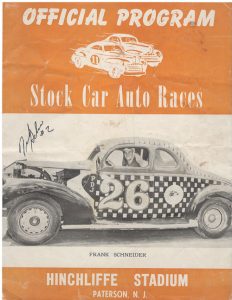

Hinchliffe Stadium in Paterson, N.J., an industrial town west of New York City with a strong racing heritage all its own, hosted auto racing on a permanent track around its ballfield beginning in 1934. Midgets were the first cars at the track, but the facility later hosted homebuilt stock cars, before racing ended there in 1951.

Built by the city of Paterson and located on an escarpment at the Great Falls of the Passaic River, Hinchliffe Stadium was declared a national historic site in 2013 and then included in the Paterson Great Falls National Historic Park, making it the only baseball venue, with or without a racing background, to become part of the National Park Service system.

In the baseball world, Hinchliffe is truly sacred, where Hall of Famer Larry Doby had his tryout before becoming the first athlete to integrate the American League when he joined the now-Cleveland Guardians, leading them to the 1948 World Series title.

Hinchliffe was the home field of the New York Black Yankees, along with the New York Cubans and the Newark Eagles, for whom Doby played. It also hosted what was then called the Colored Championship of the Nation, which pitted the Black Yankees against the Pittsburgh Crawfords in 1933.

That was a year after the city erected the 10,000-seat stadium, located in a decidedly gritty section of blue-collar Paterson, and named it for a former mayor who also ran a booming local brewery. Besides baseball, Hinchliffe hosted high school sports, at least three semipro football teams and numerous concert performances, including standup by Paterson native Lou Costello and later, the thump of Sly and the Family Stone.

Negro Leagues play continued at Hinchliffe until Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color line in 1947. A fifth-mile cinder oval was laid down oddly around the outfield and since Hinchliffe already had lights, it was a natural for racing. Ed Otto, who was already organizing midget shows at the Polo Grounds and would later co-found NASCAR, presented speedway motorcycle racing under the Hinchliffe lights in 1934.

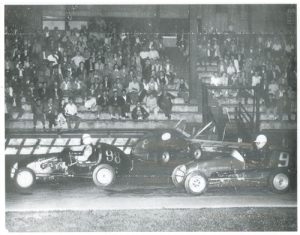

By at least one account, Otto brought the midgets to Hinchliffe for the first time in August 1934. Hinchliffe got a major boost in 1939 when the nearby, and deadly, Nutley Velodrome was forcibly shut down. The cinder track was widened, paved and later painted in a checkerboard pattern to create the illusion of speed when the races were briefly televised.

According to Brian LoPinto, director of Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium, another early Hinchliffe promoter was Jack Kochman, who later started the Hell Drivers thrill show.

Paterson’s factory ambience and hard-working populace made it a viable hub for auto racing on a couple of levels. For much of the time that racing existed at Hinchliffe, Paterson was also home to a warren of little brick and clapboard single-car garages off East 29th Street known as Gasoline Alley.

Gasoline Alley became an operating base for racers, professional and otherwise, prepping their cars for combat at Hinchliffe and elsewhere in the eastern United States.

The great Ted Horn, who amassed an astonishing nine top-five finishes in 10 starts at the Indianapolis 500, raced out of Paterson and was a Hinchliffe veteran.

Yet, Indiana native Roscoe “Pappy” Hough was probably the best-known Gasoline Alley denizen, trailering his “Five Little Pigs” brace of midgets across the country. Other Hinchliffe competitors in midgets included Dutch Schaefer and Rex Records. Another was the Los Angeles ace Perry Grimm, who won the famed Turkey Night Grand Prix at Gilmore Stadium twice, wheeling Vic Edelbrock Sr.’s nitro-urged V8-60 in the process.

It was at Hinchliffe, amid its booming midget scene, that Ken Brenn Sr., newly enshrined in the Eastern Motorsport Press Ass’n Hall of Fame as a car owner, saw some of his first racing.

“I would go there with my father when I first got my driver’s license, so it was probably 1945,” Brenn recalled. “I saw lots of nights there, many nights, when that place was full, all 10,000 seats. Some people would come wearing jackets and ties. Gasoline Alley lasted right up until the time Hinchliffe was gone. My father rooted for Johnny Ritter and I rooted for Bill Schindler. The irony is, we later ended up owning Ritter’s Offy midget together. But I don’t remember anytime I was ever at Hinchliffe when it was less than three-quarters full.”

Midgets owned Hinchliffe for most of its existence as a speedway. Schindler, the one-legged midget legend from Freeport on Long Island, led all Hinchliffe winners with 52 victories, all in midgets, according to statistics compiled by LoPinto’s group. At No. 2 on that same list is another local guy, Art Cross, who was born in Jersey City.

According to LoPinto’s list, Cross owns 47 midget wins at Hinchliffe, before he became the 500’s first rookie of the year in 1952 — one year before placing second in the classic to Bill Vukovich.

Cross is also in the record books as winner of the last major auto race conducted at Hinchliffe, dubbed the Gasoline Bowl, allegedly named in honor of Paterson’s Gasoline Alley and, according to LoPinto, run on New Year’s Day in 1950.

Cross won the ARDC-backed midget portion of the show. Jim Delaney is credited with taking the stock car segment of the Gasoline Bowl with Johnny Cabral and the future leaping, buckskin-clad flagman Tex Enright capturing heat wins.

By every indication, fans loved the stock cars and their rough-and-tumble drivers. One of them was Bill Brown of Bridgewater Township, N.J., among the last surviving veterans of Hinchliffe Stadium competition.

“When I turned 21, a friend of mine and I built an old Plymouth, a six-cylinder 1937 coupe. Back then, the stock cars were kind of hairy and scary. It was rough,” Brown remembered. “Right on the other side of the turn-two wall was the pit area and there were so many stock cars running at Hinchliffe that if you didn’t qualify and get to run in the feature that week, you had to stay home the following week and then you could come back the week after that and try to qualify again. That’s how many cars they had.

“I remember one time, some guy showed up with a little Willys coupe and the engine was mounted in the middle of the car. Every gas station around the area had some kind of basic stock car. There were so many cars, they had to park them in the streets around the stadium. You ended up pitting on the street.”

Records for stock cars at Hinchliffe are harder to find, although Brown and LoPinto both recall that the ageless Frankie Schneider, a New Jersey native, was a regular competitor and apparently, a prolific stock car winner. Hinchliffe historian Keith Majka also noted New Jersey native Bill Morrissey and Bill Holmes were Hinchliffe regulars, at least in midgets.

The track’s boom likely contributed to the downfall. Brown alluded to the local parking gridlock on race nights and Majka remembers the locals became hostile.

“I remember that before Hinchliffe closed, the mayor of Paterson campaigned on a promise to close the racing because of the noise complaints from local residents,” Majka said.

Racing ended after 1951, ostensibly to give school teams access to the property for scholastic sports. In 1963, the Paterson Board of Education took control of the stadium.

Listed as recently as 2010 as one of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s most endangered historic places, the Hinchliffe property is slated for redevelopment that preserves the ballpark while also establishing a cultural hub and new senior housing, plus a parking deck.

Paterson director of historic preservation Gianfranco Archimede assures that the completed project will recognize Hinchliffe’s racing past, even though vintage races won’t be part of it. The track is now rubberized and used by the school district for track and field events, meaning that any Hinchliffe racing reunions will remain the static displays conducted periodically to this point, largely under Majka’s tutelage.