In the United States, speedways have been variously located next to junkyards, jammed next to suburban sprawl and occasionally plopped in the middle of their hometowns.

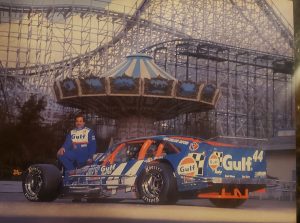

Imagine, instead, a speedway that shared its real estate with an amusement park, giving it a constant stream of potential fans, plus a picturesque location between towering rides and a lazily flowing river.

On paper, that’s failure-proof.

And for decades, Riverside Park Speedway in Agawam, Mass., was exactly that. The fans streamed, literally, straight from the rides to the bleachers. It was a can’t-miss business proposition, until amusement rides became more profitable than packed pits and stands.

And just that quickly, the track was gone, along with a significant chunk of New England’s stock car history.

“That place was just so exciting and so dramatic,” Dr. Dick Berggren, a longtime attendee and recipient of the NASCAR Hall of Fame’s Squier-Hall Award, remembered. “The drivers were characterized by maybe the best short-track announcer I’ve ever heard, a guy named Tom Galon. If there were two worms crawling out of a hole, he could turn it into a race that had you on the edge of your seat.

“It was exactly what you’d hope to have in an announcer. You knew Rene Charland was the bad guy and Buddy Krebs was a good guy. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, tonight, Jocko Maggiacomo has a new engine in his car!’ I can’t think of any race track where the drivers exhibited themselves as well as they did at Riverside.”

Riverside, both the amusement park and speedway, was an institution in its community.

It could trace its roots to just after the Civil War, when Gallup’s Grove opened as a picnic area in Agawam, nearly across the Connecticut River from the industrial city of Springfield, Mass.

Before 1900, most visitors reached the park by steamboat. The picnic grove was repurposed as an amusement park and opened its first roller coaster in 1912. After the Wall Street crash drove Riverside Park into foreclosure, one of New England’s first drive-in theaters opened on the property in 1937.

A local entrepreneur named Ed Carroll began a family dynasty at Riverside Park by buying it in 1939. That was when midgets raced seven nights a week in New England. In 1948, he tore down a bandstand on the property and laid out a flat, fifth-mile oval, just in time to see the midget craze peter out post-war.

In no way deterred, Carroll simply brought in stock cars for Riverside Park’s first full season in 1949.

The future international sports car star Phil Walters, still racing under his midget pseudonym of Ted Tappett, captured 14 of the 28 features, a record that still stood when Riverside finally closed.

Galon’s excited monologue kept fans filling Riverside Park’s 7,200 bleacher seats, creating a cast of white hats and villains that variously included Bill Greco, Dick Dixon and Danny Gallulo. The tiny, flat confines forced drivers to bump and bang their way to the front, which often triggered fisticuffs in the pit area, jammed between the backstretch and the river.

Berggren recalls seeing the same stock cars that dotted garages and gas stations in his hometown of Manchester, Conn., flailing away around Riverside’s diminutive oval.

“Before I had my license, my dad would drive me to the races and the big deal on my birthday was when I would have my friends over to the house for my mom’s spaghetti and meatballs, and then we’d go to Riverside Park and cheer for our favorites,” Berggren said. “I was just a kid and my favorite was Art Rousseau out of Keene, N.H.”

Riverside Park’s stock car era essentially existed in three phases, the first promoted by Harvey Tattersall, senior and junior, through their United Stock Car Racing Club that sanctioned tracks across New England and New York through the 1960s.

The flathead-powered stock cars evolved into modifieds; Berggren recalls the great Eddie Flemke gunning down a field of overheads with his flathead during this period. For $1.25 admission, you got to watch battles pitting Moe “Moneybags” Gherzi against Charland, driving a decidedly non-villainous coupe adorned with pink polka dots.

The natural athlete, Gene Bergin, was another star.

As Berggren recalled, Riverside had an inspired business plan: Getting inside the park was free, you only paid admission for individual rides or to enter the speedway. You grabbed food from the concessions and stopped by Shany Lorenzet’s photo booth before heading inside.

When intermission came, you hit your favorite rides, safe in the knowledge that Galon would call you back in plenty of time.

One unforgettable element of racing at Riverside was the annual 500-lap races for cars competing as two-car teams.

The spectacles lasted until the late 1970s, with Krebs leading all multiple winners with six triumphs. It was common to have up to 60 modifieds in the pits, all vying for spots in a 50-lap feature that started only 20 cars because the track was so small.

The Riverside Park track expanded every time Carroll repaved it, first to an almost-quarter with a little banking. Next, widening and steepening the corners to a full quarter-mile. NASCAR replaced the Tattersalls in 1973, following what future promoter Ben Dodge described as a drivers’ strike.

The arrival of NASCAR established Riverside as one of NASCAR’s big three modified speedways in New England, along with Stafford and Thompson in Connecticut. Ed Carroll died in 1979.

His sons then managed the park and speedway while becoming active in racing themselves, with a new crew of helpers. One of them was future FOX Sports broadcaster Mike Joy, who announced at Riverside while still in college. Joy’s assistant was Dodge, who took over as promoter in 1982.

“Things were getting very stagnant at Riverside, so they decided to introduce the pro stocks as the lead division,” Dodge explained, adding that the modified seemed a better fit at larger tracks than within Riverside’s confines. “I went in there and changed practically everything they did, and that’s when Ed Carroll Jr. asked me to become the director of auto racing. He stated to me that the race track was no longer holding its own. This would have been around 1984. I was given two years to run the race track, produce a positive bottom line and show growth.”

Dodge streamlined the modified program, marketed the competitors and started an entry-level street stock division. There was no back gate fee.

“The theory was that an entertainer doesn’t pay to walk on stage,” he explained. “Riverside Park Speedway was one of the most successful short tracks in America between 1992 and 1996. We had bigger numbers on a Saturday than the amusement park did. We had sponsorship for every race. We paid qualifying heat money.

“In addition to that, the purses were increased. My last year, 1996, the paid attendance in the grandstand was 143,000 people. We never pushed the back gate because you didn’t go in through the back gate.”

Dodge is credited with improving the payout to Riverside’s racers during the same time when the year-round profitability of amusement rides was increasingly threatening the future of auto racing. He simply says the owners decided to go in a different direction, which ultimately proved to be selling out.

Dodge, who still announces races and owns race cars, opted to take his leave, saying now that “my reign at Riverside Park was such an important part of my life that I believed it was mine. It needed help to survive. I was doing things to the very best of my ability.”

Despite the gathering fiscal clouds, the Dodge era at Riverside was spectacular, with Stan Greger, John Rosati and Mike Stefanik capturing track titles in the modifieds.

NASCAR adopted the tour-type format and Riverside was a regular stop for 200-lap modified mains. Jerry Marquis and ageless Bob Polverari emerged as big winners in the 1990s, with Polverari taking five titles aboard the Bill Pelly No. 711.

The Carroll family sold out to the Six Flags chain in 1998, two years after Dodge departed and NASCAR’s Dave Deery became Riverside Park’s final promoter. The speedway was closed, and razed, after Polverari copped the final modified feature in 1999.

When Riverside closed, Eddy Carroll III, the founder’s grandson, owned four consecutive pro stock championships.

The great Reggie Ruggiero closed the books with 98 modified feature wins, about a quarter of his career total, leading all drivers.

“I came from a little track, Plainville Stadium in Connecticut, a quarter mile,” Ruggiero remembered. “Riverside was a fifth back then. It was like going from a Volkswagen to a Cadillac; Riverside Park was like Daytona to me. I was never on a banked track, racing with that caliber of drivers before. I had my own groove, right on the bottom. The Park was what got me noticed everywhere. It was a great experience.”