It was 1972, and it was a watershed year at Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

Car builders exploring the new possibilities of aerodynamics saw opportunity abound when for the first time USAC permitted bolt-on wings. That modest change drastically affected the performance of the cars and dictates Indy car design to this day.

Overnight, wings grew to barn-door size appendages. That, combined with canny engine builders able to extract in excess of 1,200 horsepower from the ancient 160-cubic-inch turbocharged Offy engine, caused speeds to leap to astronomical levels.

Bobby Unser won the pole at a record speed of 195.940 mph, an astounding 17 mph faster than the previous mark. All 33 cars in the field qualified faster than the 1971 track record, and the race record tumbled as well, with a speed that remained unmatched for a decade.

Perhaps the most significant development in that groundbreaking year, however, was that Roger Penske won his first 500, laying the groundwork for what became a phenomenal racing legacy.

The exposure from that initial victory opened doors of opportunity that enabled Penske to build a powerful business empire, create a racing juggernaut that’s won multiple races and championships across a myriad of racing disciplines and led to an unprecedented 18 Indianapolis 500 victories.

In 2019, it was that singular success that convinced Tony George to offer ownership of Indianapolis Motor Speedway to Penske.

Penske possesses a long love affair with the speedway.

As a youngster, he first attended the 500 with his dad in the 1950s. Then, as his racing career progressed in the early 1960s, he seriously considered an offer from Clint Brawner to drive the Dean Van Lines Special at Indianapolis.

Penske opted to focus his energies on growing his businesses. That effort ultimately provided the resources to enter racing as a team owner for the first 24 Hours of Daytona in 1966.

Later that same year, at Ken Miles’ funeral, Penske spoke to a promising new driver about joining forces with him — Mark Donohue.

It was a potent pairing and soon they dominated sports car racing. In 1968, Penske shifted his attention to Indy cars and in 1969 Penske arrived at Indianapolis.

Penske and Donohue’s substantial road racing reputation preceded them, but their introduction created a cultural shock at the old Brickyard. Donohue, a crew-cut, Brown University-educated engineer, and Penske, in button-down shirt collars and button-up sweaters, were poles apart from a racing fraternity where many drivers dropped out of school to go racing, the best-dressed car owners wore cowboy hats and most perceived the “sporty car” set to be on the effeminate side.

But as Penske went about his methodical preparation with well-turned-out equipment, the behind-the-hand smirks turned to respect for his hard work, unrelenting focus and pursuit of perfection.

The results were impressive. In Penske’s first three years at Indianapolis, Donohue qualified on the front row twice and led the race on numerous occasions. Team Penske became a force to be reckoned with, but there was no Indy victory.

And, above all, Roger Penske is driven to win.

In 1972, Penske entered a pair of impeccably finished, blue trimmed in yellow, Sunoco sponsored McLarens. Penske assigned Donohue to one. Surprising many, Gary Bettenhausen got the other.

Penske had eyed Bettenhausen from the time he watched him win at Phoenix in 1968, while driving an older car for a short-budgeted team.

Tempered on the nation’s short tracks, Bettenhausen was twice a USAC national sprint car champion. Besides his considerable driving talent, Bettenhausen brought to Penske an innate ability to communicate the intricate setup nuances unique to oval racing.

From the beginning of May, the Penske drivers were among the fastest in practice. Many days Donohue and Bettenhausen exchanged quick-time honors, with Bettenhausen becoming the first driver to exceed 190 mph at the 2.5-mile track.

During qualifying, however, it was Donohue who nabbed the best starting position, nailing down the outside spot of the front row. Bettenhausen was a tick slower and lined up fourth.

With Penske’s well-earned reputation for race management, most prognosticators considered a Penske driver the favorite to win. It was only a matter of which one. On race day, Bettenhausen assumed that role.

As expected, polesitter Unser, in Dan Gurney’s Eagle, jumped into the lead, running away from the competition until ignition problems sidelined him after 31 laps. During Unser’s banzai run, Bettenhausen worked his way past Donohue and Jerry Grant, and took the lead upon Unser’s demise.

Running at record-shattering speeds, Bettenhausen pulled away from his teammate and third-place Mike Mosley. But Bettenhausen had a problem.

“About 40 laps into the race I knew we were in trouble,” explained Bettenhausen. “There was a leak in the McLaren cooling system and the engine started running hot. I radioed Roger. He said, ‘Run it till it won’t run, pal.’

“So I got out in front, thinking I could at least win some of the lap prize money before the thing quit,” continued Bettenhausen. “Then I tried a trick I’d learned while racing sprint cars. At the end of the straights, I’d hit the kill button with the throttle wide open. That flooded the valves and pistons with fuel and cooled the engine. As long as I did that, the temperature stayed down around 200 degrees.”

As the laps wound down, a palpable buzz ran through the massive crowd. Gary Bettenhausen just might win the 500. A Bettenhausen had tried getting to Indy’s victory lane since Bettenhausen’s father, Tony, first appeared at the speedway in 1946.

Tony Bettenhausen, a two-time national champion, won in every form of racing he attempted.

Yet, victory at the speedway eluded him.

In 1961, Tony Bettenhausen was quickest in practice and most believed he’d crack the elusive 150 mph barrier. But on the Friday before Pole Day, a bolt fell out of the steering of a car he was testing for a friend and Tony Bettenhausen died in a fiery crash along the frontstretch.

Bettenhausen’s father was on his mind as the laps wound down in 1972. “The car just kept running, and I thought, ‘My family has tried to win this race for so long and maybe it’s finally going to happen.’ Then the yellow came out with about 20 laps to go and it was all over. Running that slow I couldn’t keep it cool and the engine finally seized.”

Bettenhausen’s cutting disappointment was somewhat assuaged by the crowd’s support. A group of fans scaled the fence and surrounded him as he coasted to a stop near the infield fence.

“I bet I was handed 15 beers,” laughed Bettenhausen. “I climbed out of the car and sat there with those guys, drank some beer and watched the race end.”

What Bettenhausen witnessed was his teammate race into contention for the win. Running second, Donohue made a sustained charge to overtake unheralded rookie Jerry Grant, who was enjoying an exceptional race in Dan Gurney’s Mystery Eagle.

As Donohue caught Grant, he saw his head drastically lolling over from the centrifugal force in the corners. Grant was exhausted. Donohue knew Grant as a formidable competitor from their sports car days and anticipated a hard-fought shootout for the last handful of laps.

Suddenly, that scenario evaporated.

Grant dove into the pits with a bad right-front tire. In his exhaustion, he overshot his pit and slid into teammate Unser’s. The crew quickly changed the tire, but unnecessarily as they later determined, also refueled him from Unser’s pit tank. That rule infraction dropped him to 12th in the final standings.

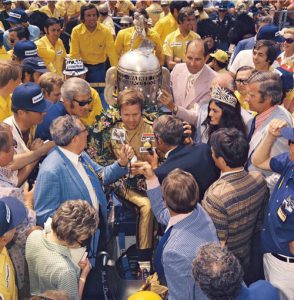

With Grant out of the mix, Donohue drove to the checkered flag, claiming his and Roger Penske’s first 500 victory.

Many thought it should’ve been Bettenhausen’s win and Donohue, typically gracious, admitted as much.

Bettenhausen said, “If I couldn’t win it, I’m glad Mark did. He helped me tremendously when I joined the team and became a good friend. We worked together well. Looking back, that got Roger’s string of 500 wins started.”

In the 50 years since, much has changed.

Bettenhausen never added his family name to the Borg-Warner Trophy before passing away in 2014. Donohue retired, returned and died driving a Penske Formula 1 car in 1975.

Some things haven’t changed, however. Penske’s intense focus to win the world’s greatest race burns just as brightly.

In 1972, his cars were among the favorites to capture the 500. That pattern continues to this day and this year he could add another Indy victory to his already remarkable record.