And to think it all started because back in the Eisenhower years, it wasn’t politically incorrect to wear fur coats.

The blossoming legion of hot rodders that were springing up all around south central Pennsylvania during the late 1950s figured they had it made because they finally had a public drag strip that welcomed their quarter-mile shootouts.

It was York U.S. 30 Dragway, which brought pro-level drag racing to an airport runway in the eponymous Pennsylvania city that’s better known for building barbells, Harley-Davidsons and Caterpillar heavy equipment.

For just under 20 years, York U.S. 30 was the weekend sanctuary for drag racers hailing from everyplace between Harrisburg and Baltimore, with a few New Jerseyans tossed in, all hammering away at each other on a runway that ran perpendicular to the famed Lincoln Highway.

Sometimes, the action would have to stop while a Cessna or Piper slowly drifted in on final approach. And sometimes, the drag cars were lined up four wide waiting for the pattern to clear. Meanwhile, guys dragging sprint cars on open trailers would honk and wave as they trundled toward nearby Lincoln Speedway.

It was paradise and the whole story starts about 30 miles from York in Lancaster, Pa., a place more closely associated with horse-drawn implements and buggies than hot rods. The story of York truly begins with the Vagabonds Car Club of Lancaster, which Dick McLaughlin founded in 1958. The club found a home, for a while, at the newly opened Lancaster Drag-O-Way, located at the then-Garden Spot Air Park along state Route 462.

By McLaughlin’s memory, the opening was a wild one, as 10,000 hot rodders jammed their way in from around the region.

It couldn’t miss — almost. McLaughlin recalls what happened next.

“Bill Holtz ran the drag strip, but there was a chinchilla farm next door to the track, and when the really loud cars ran, the chinchillas would start fighting each other and rip out their fur because of the noise,” McLaughlin said. “So the guy with the chinchilla farm took Holtz to court to get the races stopped.”

The judge concurred and drag racing at the Lancaster airport was finished, prompting Holtz to look toward the other airport, in York, and to speak with its operator, Oscar Hostetter.

It was 1959 and McLaughlin recalls that the track’s first tough guy was the famed Pennsylvania sportsman racer Jack Kulp, who at the time ran a Chevrolet panel truck stuffed with a supercharged Oldsmobile engine in the Gasser classes.

McLaughlin got a job at the track working with Chuck Lorah, Hostetter’s assistant, who, as he recalled it, “directed me to a stubby little guy with a cigar and said, ‘Go work with him.’”

McLaughlin’s first direct boss at York, therefore, was a young Bill Jenkins, who was already known as “Grumpy,” and helped the track get the incoming mass of race cars classified and staged.

Jenkins’ legendary driving career was still to come, as he worked doing dyno tuning on drag cars from throughout eastern Pennsylvania, including the early muscle Chevrolets fielded by York dealer Ammon R. Smith and slam-shifted by driver Dave Strickler.

Decades before he was the NHRA’s world champion in Funny Car, Pennsylvania racing hero Bruce Larson was another York luminary.

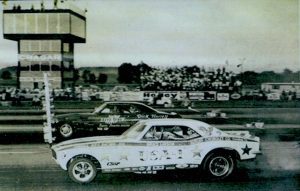

Arguably, no driver who nurtured his career at York went farther in racing than Dauphin, Pennsylvania’s Bruce Larson, who towed down from the Harrisburg area after the Chinchilla War to run his Oldsmobile-urged Chevrolet coupe in A/Gas when York was new. On his way to become the NHRA Funny Car world champion in 1989, Larson scored one of York’s most fabled triumphs when he won the 1969 Super Stock Nationals in his groundbreaking Logghe-chassis U.S.A.-1, whose Camaro bodywork still boasted functioning doors.

“York was my home track after we left Lancaster,” Larson recalled. “The Super Stock Nationals was iconic, a big deal for people all over the country before a lot of the large NHRA events existed. I managed to win it in 1969 over Dick Harrell in the other lane, and that win has kind of lived with my career for years thereafter. We’ve really missed York, ever since it closed in 1979.”

There were scores of less-known racers from car clubs, including the Gents of Hanover, Motor Menders of York and the Sportsters, also of York.