NASCAR Hall of Fame historian Buz McKim offers insight into what was considered a heavy luxury car in its day.

“If you look at the Hudson Hornet as it sat, you wouldn’t think it would be a great race car,” McKim said. “It had a flathead six-cylinder engine and low-end torque, which was good on short tracks. Also it had the factory Twin-H carburetion system so they were able to run two carburetors. Also, they had the step-down design for the interior. Instead of having the floor sit on top of the frame rail, it was between the rails, which lowered the center or gravity and gave it a tremendous handling advantage. A combination of all those features made the car absolutely fly on the race track.”

The car had a great design but Teague saw the potential the car had as far as racing it. He worked with engineers to develop the Twin H. When he won on Florida’s Daytona Beach in 1951, he was sure they had come up with something special.

One of the most unique cars to race in NASCAR was the Tucker. Known as the 48 or Tucker Torpedo, it was developed by designer and entrepreneur Preston Tucker. Joe Marola entered a Tucker in one NASCAR event at Canfield, Ohio, on May 30, 1950, but finished last after falling out on the first of 200 laps.

In the 1930s, Tucker worked with famed race car designer Harry Miller, a nine-time winner at Indianapolis. Having seen riding mechanics in Miller’s cars, there was an area under the dash on the passenger side for them to crawl into in the event of a crash. Tucker incorporated the idea into his passenger cars, an area of Miller’s cars commonly dubbed “going to the basement.”

Another of the unique cars utilized in NASCAR’s premier series was a Ford Edsel convertible driven by Indianapolis native Paul Bass in the inaugural Daytona 500 on Feb. 22, 1959.

It is believed to be the only time an Edsel was entered in NASCAR competition. Also in that event, Ohio native Harold Smith drove a Studebaker Lark to a 31st-place finish in the 59-car field. Eight years earlier in 1951, Frank Mundy scored a win for Studebaker in Columbia, S.C.

Aside from Curtis Turner’s 1951 win at the Charlotte Fairgrounds in a Nash Ambassador, a next generation modern-era American Motors race car didn’t appear in NASCAR until 1972.

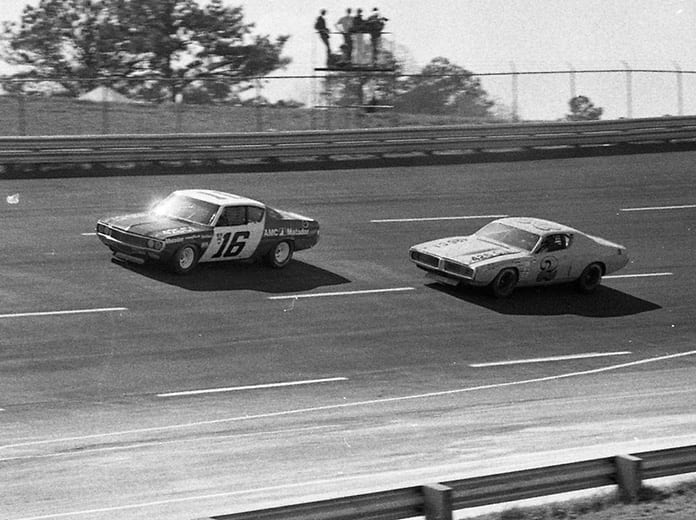

Roger Penske fielded Matadors through 1975 with drivers Mark Donohue, Dave Marcis, Gary Bettenhausen and Bobby Allison. Among fans, the little “Bull Fighter” was wildly popular.

Allison alternated between driving own Chevrolets and the Matador for Penske in 1974. After a year of driving Mercurys for Penske in 1976, Allison fielded his own Matadors throughout the full Cup Series schedule in 1977.

During the car’s heyday, Donohue and Allison drove Matadors to five victories. The first came with Donohue at the now defunct Riverside Int’l Raceway road course in California in January 1973.

“Throughout its time in NASCAR, the AMC Matador was considered to be an underdog,” Allison said. “But I think it was a good fit for me because I sort of considered myself an underdog based on some of the things that happened in my career.

“During the entire venture, some people had a negative attitude toward the car about its ability to battle against GM, Ford and Chrysler,” Allison added. “They adapted the attitude the Matador just wasn’t good enough. I didn’t believe that. I thought the car had great potential and being able to win with it proved that.”

Allison, the 1983 Cup Series champion, logged three of his 85 victories in the Matador.

“By the time we won those races at Darlington, Roger (Penske) was allowing me to select my own chassis setups,” Allison said. “Most everywhere, the car ran good and handled good. We did discover a problem with the engine’s rocker arms, but we were able to get a little more reliability out of them as time went on.”

The automotive industry in the years after World War II saw several new automakers come into the fold. McKim speculates on a number of scenarios that could have been the motivation for passenger cars to become racers in that era.

“Racing an odd car every now and then was in part because someone wanted that Cinderella finish or maybe felt the car offered some advantage on the track,” McKim said. “Other cars came from a family member that allowed someone to race it, while some had friends that were car dealers willing to give them a car to race. Having something unusual to drive would also draw more attention or notoriety whether they won or didn’t win.”