On Sept. 8 in Newark, N.J., Hasha was leading the day’s final race when his engine sputtered. He slowed to adjust the carburetor and headed back into action. Inexplicably, he shot up the track, rode up and along the rail for a hundred feet, clipping the heads of dozens of spectators. Hasha was slung into the crowd while his bike floundered down the track in front of John Albright.

When the dust cleared, Hasha and Albright were dead, along with six spectators, three of which were young boys. Thirteen others were injured.

The tragedy made the front page of the New York Times and was quickly picked up by papers across the country. The outcry was immense. A few months later, in Ludlow, Ky., another tragic accident raised the clamor to shrieking levels.

Star rider Oden Johnson hit and sheared a light pole. The dangling — still hot wires — set leaking fuel from the bike’s gas tank ablaze. Johnson, the bike and the blazing tank were flung into the crowd. Johnson and seven fans died. Thirty-five were seriously burned.

One sensational fatal accident followed another with the gory details plastered in newspapers across the country. One article titled, “Thrills and Funerals” carried the names of riders and fans killed in the previous 12 months. Lawsuits were filed, legislators were outraged and some local authorities shut motordromes down.

Still, daring young men continued to throw a leg over their bikes and race, while thousands cheered them. Despite desperate safety measures enacted by tracks, the deaths continued. Finally, in 1919, the major sanctioning body, the Motorcycle and Allied Trades Ass’n, refused to sanction motordrome races.

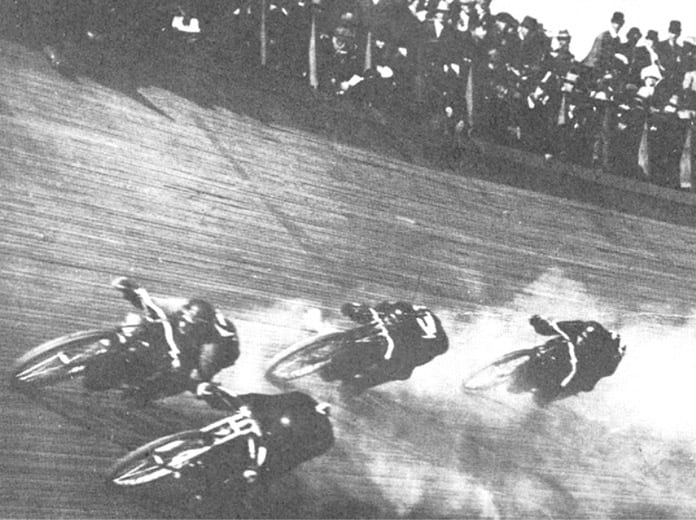

Board track racing continued, however, on larger tracks like Beverly Hills —tracks with straights where spectators could be seated out of the line of fire. For the riders, however, the danger remained. With new technology, speeds climbed. Riders raced within inches of each other on oil-slickened boards, skewed by flying splinters, protected only by a leather helmet, boots and a heavy sweater.

At Beverly Hills Speedway on April 24, 1921, the day’s programs were marred with numerous crashes. Fan favorite Burns won early and then crashed hard in another heat. He was hauled to the hospital with severe cuts, abrasions and full of large splinters.

He was out for the day, but alive.

Then, just before the final race and to the excitement of the crowd, Burns appeared. Heavily bandaged, he taped a chunk of foam rubber to the fuel tank to offer some comfort and charged through the field to take the win.

The roar of the crowd could be heard above the constant buzz of the bikes. He was the hero of the day. In a few months, however, the 24-year-old was dead. Claimed by a crash on a Toledo, Ohio, board track.

By the late 1920s most of the board tracks were gone. Not because of the scores of deaths, but because they proved as fragile as the men who raced on them. Some were lost to storms, some to fires, most to simple deterioration.

Wood rotted. Machines crashed. Men died. And one of the most thrilling, dramatic, deadly eras in motorsports came to an end.