Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in the July 2016 edition of SPEED SPORT Magazine.

Within sight of the Hollywood Hills where the Beverly Wilshire Hotel stands today, fans filled California’s Beverly Hills Speedway on April 24, 1921, for an afternoon of drama-charged two-wheeled competition.

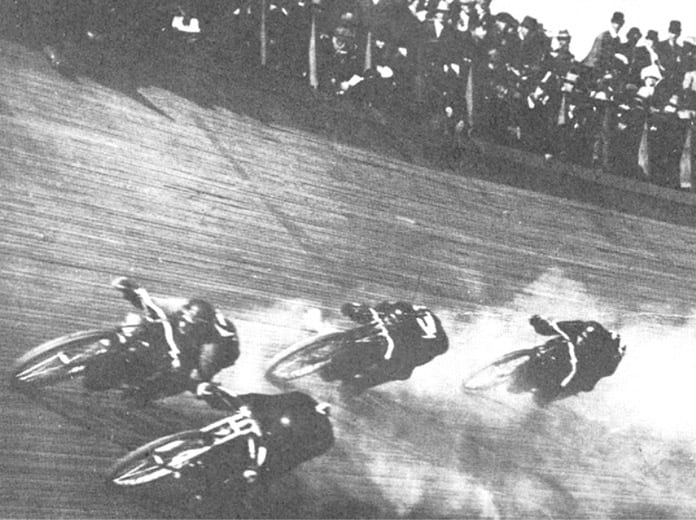

Constructed entirely of wood, the surface of the 1.125-mile track consisted of two-by-fours laid on edge and the turns soared 45 feet into the sunny, Southern California sky. With turns banked at 37 degrees — in comparison the turns at Talladega (Ala.) Superspeedway are banked at 33 degrees — the speeds were frightening and incredible.

Motorcycles were topping 110 mph as the men who clung to the fragile-appearing machines in the flowery prose of the 1920s, “raced neck to neck with death.”

Board track motorcycle racers were extreme sports stars decades before there were extreme sports. They took incalculable risks. Their mounts were no more than a frame, two wheels and an engine. To further lighten them, they had no transmissions, no clutch and no brakes. To slow down or stop, the fearless riders relied only on an engine kill switch mounted on the handlebar.

Albert “Shrimp” Burns, Jake DeRosier, Charles Balke, Eddie Hasha and many more amazed the country with their 100 mph exploits on the “wooden walls” as some tracks were banked as much as 60 degrees. They were heroes. Household names who earned $20,000 annually, equivalent to a half-million in today’s dollars.

Their bravado, combined with that generation’s lust for motorized speed in the formative years of the automobile and motorcycle, drew 50,000 to Beverly Hills that April afternoon and attracted capacity crowds to similar facilities across the country.

Motorcycle board tracks, all the rage in the early part of the 20th century, came about out of necessity. Motorcycle racing on public roads had been legislated out of existence and the bicycle velodromes were too small to handle the motorcycle’s dramatically increasing horsepower.

The first large board track built specifically for motorized competition was constructed in 1910 near Playa del Ray, Calif. Designed by famed bicycle velodrome builder Jack Prince, it was called the Los Angeles Motordrome. It was a perfect circle and a mile in distance. A fleet of carpenters used 3 million feet of lumber and 16 tons of nails to build it. Banked at 20 degrees, it was a marvel for its time.

The first major motorcycle event, run on May 8, 1910, drew a capacity crowd to the 40,000-seat facility to watch a series of events. DeRosier, on a factory Indian, roared to a speed record of 90 mph for the mile.

However, that record was short-lived. In a few months, Hasha took his Indian to 95 mph and shortly after that Lee Humiston topped 100 mph on an Excelsior. It was years before race cars came near those speeds on the boards.

With the success of Los Angeles Motordrome, similar tracks sprang up like mushrooms after a spring rain. They were inexpensive and quick to construct. One in Salt Lake City was built for $100,000 in two weeks. Modeled after Los Angels, motordromes soon appeared in cities big and small.

Almost immediately the weakness of their “pie pan” design, in regards to safety, became evident. Grandstands were perched on the top and at the edge of the track. Spectators crowded right against the guardrails, with only two-by-fours strung between posts, to experience up close the thrill of motorcycles roaring by at 100 mph.

It made for spectacular viewing until a motorcycle, constantly in a state of centrifugal force with a trajectory directly toward the crowd, went out of control. The results were often horribly lethal. Death became so common that the motordromes were tagged “Murderdromes” by the press and the outcry against the carnage grew so vociferous that it led to the demise of the sport.

On Sept. 5, 1912, at Salt Lake City’s motordrome, Harry Davis lost control and his bike catapulted into the crowd. Davis died and seven spectators were injured.

It got worse.

Click below to keep reading.