Auto racing has long attracted colorful, eccentric, quirky individuals. They seem drawn to the sport like steel shavings to a magnet.

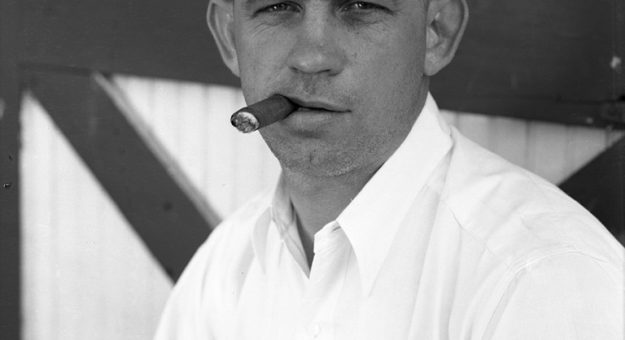

Few better fit that offbeat category than Arthur Sutton Sparks.

Quick-tempered, raucous and adventuresome, he raced on outlaw dirt tracks, performed as a movie stuntman and was a fearless gambler with a deck of cards and his professional choices. Sparks did at least two stints in jail, yet created some of the most innovative, successful race cars conceived in American racing.

Born in Los Angeles in 1900, he was a true hell-raiser. “All I wanted to do was fool with cars and motorcycles,” he said.

Sparks floundered finding his life direction. He scraped through high school, then tried college. But after two weeks he encountered a pretty 17-year-old woman in a Berkeley, Calif., drugstore, married her and booked a cruise to the Orient.

With 10 grand in his pocket, intended as his college fund from his hotel-owner father, the ship’s poker tables beckoned. During the trip, Sparks lost the $10,000 and another $3,000 borrowed from the ship’s purser as well.

Flat broke when the ship returned to San Francisco, he was jailed. To teach him a hard lesson, his father allowed him to sit behind bars for two months before bailing him out.

After that episode, Sparks again enrolled in college, his sights set on becoming a doctor. That pursuit lasted only a short time, however, before he again dropped out.

He moved to L.A., and as fate would have it while cruising Hollywood on his Harley, an executive from the Famous Players-Lasky studio spotted the 6-foot, 200-pound Sparks, and thought him perfect for a spot in a Will Rogers movie that was being shot.

Offered $50 a day, Sparks launched his Hollywood stuntman career. He jumped motorcycles, crashed cars and walked airplane wings in 50 movies, including Howard Hughes’ epic, “Hell’s Angels.”

Skills he acquired while “fooling around with cars and motorcycles” as a youth, landed him a job teaching shop at Glendale High School. It supplemented his stuntman income, but more importantly, provided him complete access to the school’s machining equipment.

With that tooling, Sparks built his first race car, including machining the parts for the engine he designed himself. He debuted as a driver in late 1927, but three crashes in four races convinced him to leave the driving to others.

In 1930, Sparks quit his teaching and stunt duties to focus solely on racing. Paul Weirick funded the operation, while Sparks designed and built the cars.

The partners were at the forefront of the wildly popular, exceptionally competitive racing at the infamous Legion Ascot Speedway, a lightning-fast, often lethal, five-eighths-mile oval.

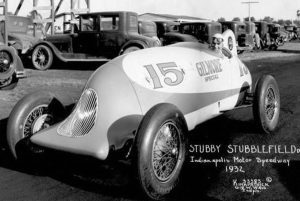

With drivers the caliber of “Stubby” Stubblefield, Bill Cummins and Rex Mays, the team won scores of races, set dozens of track records and captured three AAA Pacific Coast championships.

That success inspired Sparks to try Indianapolis. He designed a car with a groundbreaking aerodynamic shape derived from data he collected in Stanford University’s wind tunnel.

Dubbed “The Catfish,” Stubblefield pushed it to sixth in the 1932 500 before a fuel leak stopped him on lap 178.

During the following years, as a consequence of his drama-filled lifestyle that he couldn’t seem to moderate, Sparks was in and out of Indianapolis competition. He spent a day in jail after a run-in with the IRS, served a two-year AAA suspension and finally sold his partnership share to Weirick after one too many raging “discussions.”

Using those funds, Sparks built an Indianapolis car powered by a straight-six engine of his own design. Jimmy Snider qualified it late, but was fastest in the 1937 field by an incredible 5 mph. Snider roared past 18 cars on the first lap and grabbed the lead, but the car broke early.

That performance attracted the attention of irascible 23-year-old, Chase Manhattan Bank heir, Joel Thorne. Perhaps more eccentric than Sparks, Thorne once paid off a debt with a wheelbarrow load of pennies, the racing community gave little credence to their announced “lifetime contract.

As expected, their agreement was short-lived. Yet, Thorne’s finances enabled Sparks to display his brilliance at creating fast, innovative cars, eventually winning the 1946 Indianapolis 500 with George Robson driving. It was Sparks and Thorne’s last venture together.

In 1949, Sparks reinvented himself as a businessman and remained a force in racing until his death with his ForgedTrue pistons, used in every discipline of the sport and in the engines of 11 consecutive Indianapolis 500 winners.

This story appeared in the March 1, 2023 edition of the SPEED SPORT Insider.