Editor’s Note: NASCAR is celebrating its 75th anniversary in 2023. SPEED SPORT was founded in 1934 and was already on its way to becoming America’s Motorsports Authority when NASCAR was formed. As a result, we will bring you Part 13 of a 75-part series on the history of NASCAR as told in the pages of National Speed Sport News and SPEED SPORT Magazine.

The 1960 NASCAR season raced by faster than ever.

Glenn “Fireball” Roberts raised the speed bar in stock car racing over the 150 mph mark on Jan. 31 when he ran around the Daytona Int’l Speedway’s 2.5-mile course during the third lap of a 10-lap Grand National race at 152.161 mph. Roberts returned to Daytona six days later and set an American two-lap stock car record of 151.556 mph while qualifying for the Daytona 500 in a 1960 Pontiac Bonneville.

Two-time Grand National champion Buck Baker talked about the reason behind the record speeds reached at the superspeedway in the Feb. 10 issue of NSSN: “It is 10 tracks in one and they are all good. If a driver drives it high, he is all right. If he drives low, he is fine, and if he sticks to the middle he is in as good a place as any. There is no such thing as a groove, as there is at all the other tracks I have driven.”

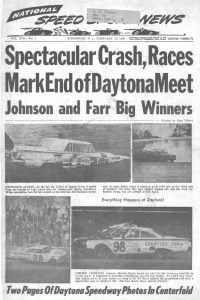

Yet, driving at speeds once thought impossible to achieve, or at least ludicrous to attempt, produced greater danger to the driver. Testament to this concern was the second annual Daytona 500 in which 21 accidents occurred before Robert “Junior” Johnson drove his 1959 Chevrolet under the checkers in first place.

The always-windy conditions may have contributed to the wrecks, but popular driver Marshall Teague’s death while trying to better his Daytona Int’l Speedway non-stock car one-lap record of 171.821 mph, in a Sumar streamliner, combined with the monumental number of accidents this season begged the question: Is Daytona safe?

“(Daytona) couldn’t be safer,” commented veteran pilot Baker. However, he added, “the danger comes when drivers suddenly find themselves going 10, 15, 20 mph faster than they ever traveled before and don’t realize that at 140 and above the margin for error is cut down a powerful lot.”

Fortunately, as greater risks arose in automobile racing, came innovations designed to aid and protect the drivers. Firestone Tire Co. designed a new tire just for Daytona and the other high-banked, paved superspeedways in Charlotte, N.C., Atlanta and Hanford, Calif., which hosted NASCAR Grand National races for the first time in 1960.

The tire used a wider tread for more traction on the smooth banks and straightaways of these speed plants. Guaranteed up to 160 mph, this innovation led to Jack Smith’s record 146.842 mph average in his victory in the Firecracker 250 on July 4 at Daytona.

France Establishes Minimum Weight Requirement For NASCAR

The peril all drivers put themselves at behind the wheel did not escape the attention of Bill France. The March 23 issue of NSSN cited an article which France penned for Mechanix Illustrated. In the piece, he called for a minimum weight for all race cars to provide better grip on the track and for strengthened and extended roll bars.

France advocated the addition of frames around steel with rubber or glass fiber fuel tanks to prevent ruptures. In the case of fire, he called for automatic or manual-operation carbon dioxide tanks near the engines and fuel tanks of the cars along with water in the cockpit for the driver to douse himself should he catch fire.

Despite the dangers, the NASCAR Grand National season proceeded with a full slate of 47 races, minus three events in March which were snowed out. Of the remaining 44, Rex White and Richard Petty each made 40.

Petty Falls From First, White Moves Into The Lead

The lean and handsome son of the defending division champion appeared on his way to his first title behind the wheel of a Plymouth, when he was disqualified after the inaugural World 600 at Charlotte Motor Speedway.

During the race, Petty drove his No. 43 across a section of the grassy infield to pit after a tire blowout, rather than continue around the 1.5-mile circuit and enter through the pit area entrance. His move was declared illegal after the event and the points he earned were withdrawn from his season total. Thus, he fell from first to fourth in the points race.

Meanwhile, the 5-foot, 4-inch White, who appeared a non-factor in the title chase for the first five months of the season, moved into the top spot. The diminutive pilot, who was voted the most popular driver this season, stood tall in his new position and claimed five victories in the final 20 races to bring his total to six triumphs on the season.

His scores, added to 35 top-10 finishes, propelled him to the NASCAR Grand National championship.

NASCAR’s three other national divisions, sans the convertibles this year, crowned former sportsman champ Johnny Roberts as the modified king. Berni Wilhelmi won the midget class and New Yorker Bill Wimble earned the sportsman season title.

Notably, NASCAR races appeared on network television for the first time this season. On Jan. 31, CBS Sports televised, live, the race in which Roberts broke 150 mph along with another 10-lap late model race and two 10-lap compact car features as part of a special CBS Sports Spectacular program with Walter Cronkite as one of the announcers.

Two weeks later, NBC Sports filmed the four-lap Autolite Challenge, also at Daytona Int’l Speedway, and broadcast it during the telecast of the Today Show.

Lee Petty was named the stock car driver of the year despite finishing sixth in the Grand National points and 26-year-old David Pearson became the rookie of the year.

The Loss Of Legends

NASCAR lost two legends in 1960. Erwin George “Cannonball” Baker died of a heart attack at the age of 78. Commissioner of NASCAR since its inception in 1947, Cannonball held more records and medals from automobile and motorcycle racing than anyone.

Robert (Red) Byron, 44, also died of a heart attack. Byron won the first NASCAR-sanctioned race, averaging 74.94 mph at the old Daytona beach-and-road course. He was the NASCAR modified titlist in 1948 and the Grand National champion in 1949.

In NASCAR’s 13th season, it became clear that the construction of the superspeedways and the unprecedented speeds attained on these tracks had altered NASCAR’s present and future.