NASCAR’s speedy rise in popularity first captured the attention of those outside the automobile racing world in 1952.

What existed only five years earlier as an unorganized collection of tracks, promoters and drivers competing against each other under criteria which differed from track to track emerged as unified divisions of cars racing at NASCAR-sanctioned tracks under clear guidelines.

Now competitors knew that all the cars on the track raced under equivalent specifications for a guaranteed purse. Fans flocked to the events because the drivers in the strictly stock division raced the same cars around the track which they drove to church on Sunday morning.

Hence, because the track served as a testing ground for automobiles and as a result of the year-by-year increase in the attendance at NASCAR Grand National events, NASCAR attracted the eyes of American business.

NSSN first reported this trend in the Jan. 16 issue: “The automobile industry, which began keeping its eye on NASCAR’s Grand National Circuit races in 1951, will give even more special attention to these strictly car races this year (because) you can’t find a better proving ground for their products.”

This expanded Bill France’s original vision of simply attracting a greater fan base by racing late-model, strictly-stock cars. More importantly, with corporate involvement came legitimacy in the eyes of public officials who sought to limit or halt racing’s expansion in communities across the country.

Also, the automobile manufacturer’s interest in NASCAR generated national publicity for the organization which was pushing its products to the limit in every race.

Earning The Eyes Of The Industry

Two months after NSSN heralded the future between NASCAR and the auto manufacturers, the Champion Spark Plug Company signed on as a point-fund prize contributor. Champion Vice President James F. Lewis Jr. noted the same reason as the car makers for their alliance with NASCAR: “We believe that the grueling tests given spark plugs in every NASCAR race makes a fine laboratory for our engineers.”

Champion’s agreement added $5,000 to the championship points fund with $1,500 allotted for the Grand National division.

Before the end of 1952, the Wynn Oil am Miracle of Power companies also agreed to enhance the championship prizes.

Amid the growth, the NASCAR hierarchy remembered the reason for its growth, namely, the fans.

NASCAR President Bill France encouraged a big-picture approach by the drivers in their dealings with the public when he addressed the annual awards banquet audience: “The day of the outlaw is past. You fellows are members of an organization which has the eyes of the motor industry (and their customers — the fans) on it.”

Soon after France’s pronouncement, the Feb. 27 issue of NSSN printed NASCAR Executive Secretary Bill Tuthill’s announcement of the Fan Membership Plan designed to increase fan interest and knowledge.

Tuthill said, “Even though auto racing has now taken a place among the major spectator sports of the country, the racing fan still knows less about the sport than fans of any other sport … until now, no major racing organization has recognized this problem or made an attempt to do something about it.”

Under the plan, members received bulletins, newsletters, a rules book and discounts on motorsport magazines and auto accessories.

This proactive approach to fan relations made NASCAR a standout in the sport of racing.

The standouts in the Grand National cars began the race schedule in January on the half-mile track in West Palm Beach, Fla., rather than on the beach road Daytona Beach course in February.

Tim Flock’s Streak

At West Palm Beach, Tim Flock pushed his 1952 Hudson Hornet to the first of eight victories on the season.

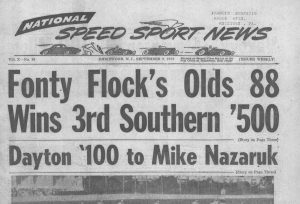

After his early victory, Flock failed to visit victory lane in his No. 91 car for five months. His winless streak forced him to third in the championship fight behind Lee Petty and his older brother, the flamboyant Fonty Flock, who sported an Errol Flynn-style mustache and drove to victory in the Southern 500 wearing white satin shorts and a matching sport shirt.

Undeterred by his 12-race winless streak in the first half of the season, 28-year-old Tim Flock began a run of seven victories in 10 starts with his June 1 triumph in Toledo, Ohio.

At the end of the 34-race schedule, this midseason surge placed Flock in front of eight-race victor Herb Thomas. Most popular driver award winner Petty faded to third and Fonty Flock claimed fourth in the points race despite driving for much of the season with one hand after dislocating his shoulder in a crash.

The growth and prosperity in the Grand National division was shared in NASCAR’s other divisions as the point fund reached an all-time high of $55,789. Among those who shared in the wealth were sportsman division champion Mike Klapak, who reigned for the third year in a row, Frank Schneider in the modified division and Neil Cole in the Short Track Division.

Former taxi cab driver Buck Baker emerged in the new Speedway Division, which ran Indy-style cars with American passenger-car engines.

Overall, the year was best summarized by NASCAR Public Relations Director Bill Schubert who asked in the Dec. 3 NSSN: “How much bigger can NASCAR get?”

Editor’s Note: NASCAR is celebrating its 75th anniversary in 2023. SPEED SPORT was founded in 1934 and was already on its way to becoming America’s Motorsports Authority when NASCAR was formed. As a result, we will bring you chapter 5 of a 75-part series on the history of NASCAR as told in the pages of National Speed Sport News and SPEED SPORT Magazine.