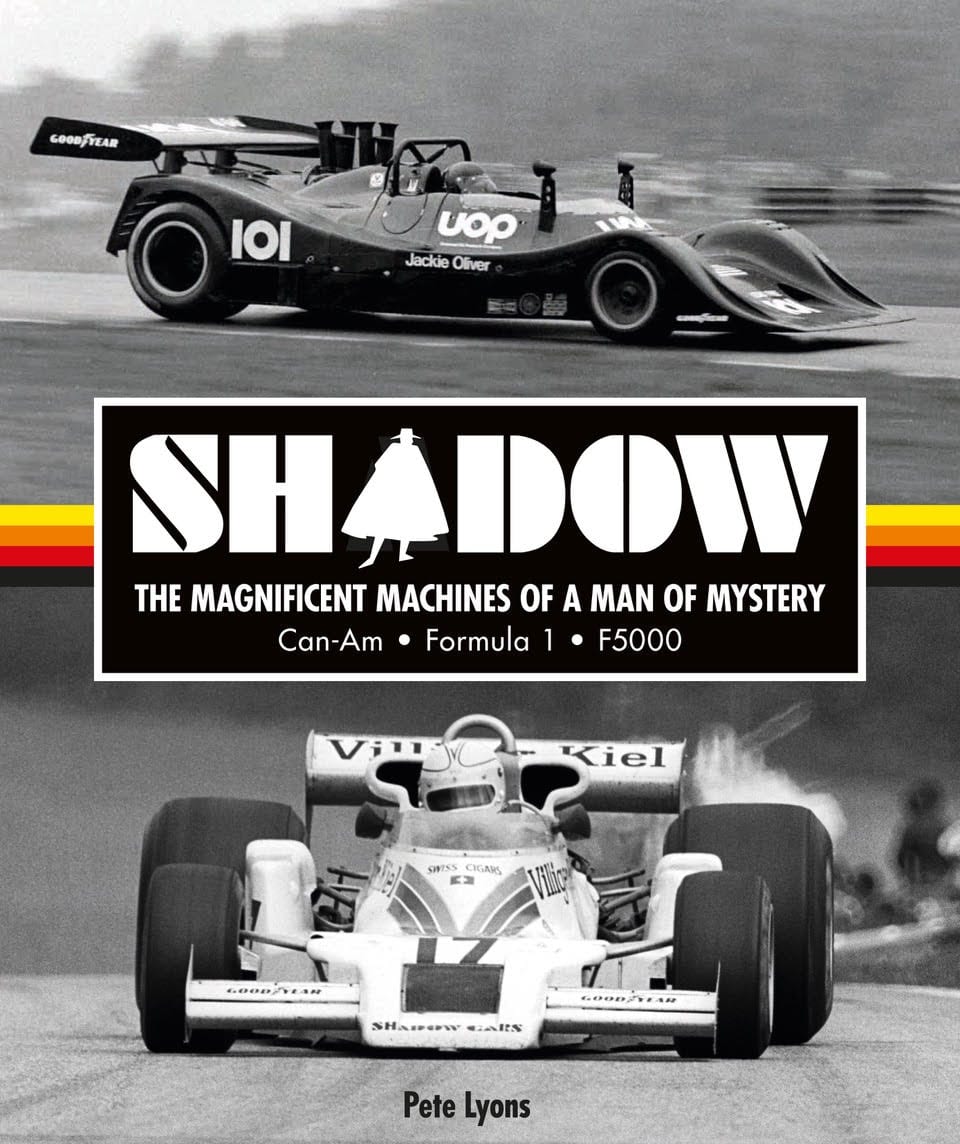

“SHADOW: THE MAGNIFICENT MACHINES OF A MAN OF MYSTERY,” is the first complete story of the enigmatic Don Nichols and his iconic American race team — and it’s written by a reporter and photographer who was there in the day: Pete Lyons.

“SHADOW: THE MAGNIFICENT MACHINES OF A MAN OF MYSTERY,” is the first complete story of the enigmatic Don Nichols and his iconic American race team — and it’s written by a reporter and photographer who was there in the day: Pete Lyons.

As a working race reporter and photographer, I witnessed Shadow’s debut in 1970, when George Follmer drove the astonishingly novel “Tiny Tire” AVS Shadow Mark 1 in Mosport’s Can-Am event. Three years later, I covered Shadow’s debut in Formula One during the 1973 South African Grand Prix, when George and a model DN1 took his and the team’s first world championship point.

I covered the races, I studied the cars, I knew the people — Nichols himself, his drivers, his designers and many of the indefatigable Shadowmen of the team. I watched Shadows racing at unforgettable circuits across the globe. Great memories. Great cars. Great people.

And, long years after, my wife, Lorna, and I were privileged to spend many days with the aged but still active “Shadowman” himself at his storied “Wizards Cave” near Monterey, Calif. We heard Don Nichols’ life story told by the man himself. And what a story it is …

The following is extracted from Chapter 5 of “SHADOW: THE MAGNIFICENT MACHINES OF A MAN OF MYSTERY

Shadow’s Short, Sad Season Of ’70

JUNE 14, RACE DAY for the opening round of the new Can-Am season was coming up fast. The venue would be Canada’s Mosport Park, almost as far from Southern California as one can drive, a long haul diagonally across all of North America, past Toronto in Ontario province.

But the Shadow program, seemingly once so comfortable, was now in serious financial distress.

Despite months of hard work to make presentations nationwide, which secured a few enthusiastic handshakes but no signed contracts, Nichols had not landed a corporate sponsor. He had committed to cover shortfalls himself, expecting to rely on regular payments from his old Japanese business. But the caretaker he left in charge in Tokyo wasn’t doing the job. The AVS office telex machine was kept smoking with trans-Pacific queries and assurances, and at one point a promise came through that a check had been sent. But only the promise ever arrived.

Near the end of 1969, Nichols realized the “$40,000 to $50,000” initial budget that (Trevor) Harris had casually suggested was swollen gargantually. In later years, Don said he had spent a million dollars. A more contemporary source, a 1971 article in Road & Track, puts the figure at half that. Either way, in those days it was a fair chunk of change to squander.

To be fair to Trevor (Harris), he had been asked for an estimate to build one car. It had been Don’s decision to set up a small factory with all necessary equipment, hire the best staff, build several chassis and go professional racing at the top level.

But that’s the way the man was. Characteristically, he “celebrated” his financial problem by putting prominent “$” signs in the test car’s number roundels. Forever after, Nichols gleefully called this “the Dollar Car.”

But by springtime 1970, he was truly running out of money. Key personnel left. Only a faithful skeleton staff remained. These included Harris, determined to see it through; a trained engineer and keen amateur racer named Jim Mederer; and “Teji,” short for Noritchka Tejima, a faithful young mechanic whom Nichols had befriended in Japan. Only they would be going to Canada with Nichols.

Pre-race preparations were still underway when Sheriff’s Deputies appeared at the door. Earlier, Nichols had engaged an architect to spruce up his Palos Verdes home, but couldn’t (or wouldn’t) pay for the job. The lawmen presented a court order to seize two Shadow race cars and showed a copy of the Japanese magazine Auto Sport showing the pair they wanted. One was a partly-assembled orange car bearing No. 2, the other what looked like a complete, race-ready black vehicle No. 1.

“Of course, that was never a real car,” says Trevor with his trademark grin about the latter, which had also appeared on the cover of Road & Track. “It was just Wayne Hartman’s body buck painted up in black to cover the Bondo and mounted on a fake chassis he made of out of plywood. I don’t remember how he made the wheels, but they weren’t real either.”

As fellow Shadow employee Kent Telford would later write in his own Road & Track story, quoted here in another chapter, that black-bodied mockup was on display in the shop, so to the court it would satisfy half the judgement. Apparently, nothing else in sight was clearly the orange vehicle, a least to layman’s eyes, so the “Shadowman” realized they had an opportunity to exercise a little racer’s ingenuity. Trevor grins again as he tells the tale:

“We quickly knocked up a crude frame out of square tubing and draped one of our genuine production bodies over it. I did the welding. It wasn’t the best job of welding I ever did.”

Meanwhile, out of sight, measures were being taken to secure the team’s single running, race-ready machine, the same “Dollar Car” used for all the testing. Time was too short to build another — but long enough to worry that the plaintiff would realize he had been conned.

“SHADOW: The Magnificent Machines of a Man of Mystery,” is available in the U.S. from specialist and online booksellers. It is also available directly from the author, at petelyons.com.